Inside the neoliberal mind part 1 – the rebranding of failure.

March 24, 2015

Troika economists have a problem. It’s huge: cutting wages clearly did not work as intended, which goes against their deepest convictions. In such a situation people tend to rationalize. To quote Goethe: “intelligent people are sharpest when they are… wrong“. Some recent publications enable us to investigate the rationalization process of among others ECB economists. One of these is a Voxeu piece by Eric Bartelsman (head of the department of economics of the Vrije Universiteit van Amsterdam), Filippo di Mauro (senior advisor in the research department, ECB) and Ettorre Durucci (head of the convergence and competitiveness division, ECB) which clearly shows that cutting wages did not work as intended (see their figure 1). How did they cope with this?

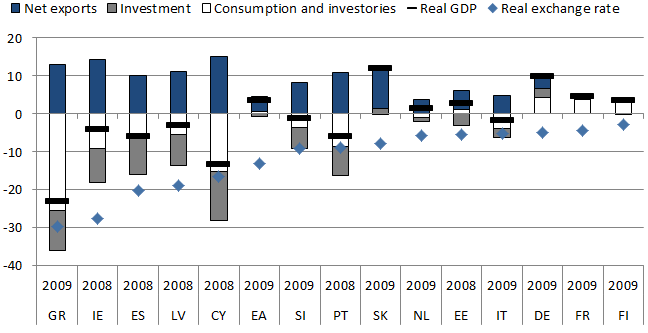

Figure 1. Relative prices and activity in selected Eurozone countries (change between the year of the ULCT-deflated REER peak and 2014 projected)

Figure 1 shows that

* As a consequence of austerity the ‘Real Effective Exchange Rate (REER)’ of countries like Spain, Ireland, Greece, Latvia and the like declined a lot (i.e.: exports became much cheaper). This was totally intended.

* But this did not lead to the expected increase in net (!) exports, an increase which, implicit in their text, should (together with an export and low wages induced private non-construction investment boom of at least 100%) have been enough to compensate the decline in wage income as well as the building bust and the government spending cuts. Mind that the increase of net exports was generally not caused by an increase of gross exports but to a decline of gross imports.

How do they explain this? Easy: the authors state that austerity damaged the austerity economies to such an extent that they just can’t export anymore, blame this on rigidities and plead for… even more austerity and reforms. A quote (text directly below the graph in the original article):

What happened? Our suggested narrative is that the deterioration of competitiveness during the credit boom left the imbalanced countries, when the financial cycle turned, with no alternative but to pursue internal devaluation. Given labour and product market rigidities, however, the adjustment was initially driven more by compression of demand than by a reduction of costs relative to the other Eurozone countries and the rest of the world. The ensuing shortfall of investment, coupled with labour market hysteresis, produced a significant contraction in potential output.

what’s wrong with this rationalization?

A) In a global perspective all exports boil down to domestic demand

B) A severe decline in investment is a pretty consistent characteristic of the downturn of the business cycle – expecting an increase in such a situation is an idiosyncratic mental attitude.

Ad A) After 2008 a whole lot of neighbouring ‘stressed’ Eurozone countries simultaneously severely restricted domestic demand and/or were coping with the consequences of a severe decline of construction investment. This, of course, led to a decline of imports – and therewith of course to a decline of exports of other countries. At the same time countries like the Netherlands and Germany also restricted demand (government cuts, wage moderation, households which were deleveraging), North African countries were in disarray and other large customers like the UK and the USA had only barely recovered from the 2008 slump. Expecting fast growth in net exports led by double-digit increases in gross exports in such a situation is naïve – not to say superstitious.

Ad B) A strong decline of investment is a pretty universal characteristic of a downswing of the business cycle. Just check the Eurostat data. This is not caused by a ‘lack’ of flexibility but by the combination of a lack of demand, liquidity constraints, lack of confidence etcetera. Expecting an increase of investments during the most severe post WW II business cycle downturn in Europe shows an incomprehensible lack of historical knowledge. Expecting an upswing of private non-construction investment that compensates for the decline in construction investment as well as government investment plus part of the decline of consumption borders on superstition. See also this ECB study published today which shows (according to the abstract, haven’t read the rest) that government consolidation leads to a decline of confidence.

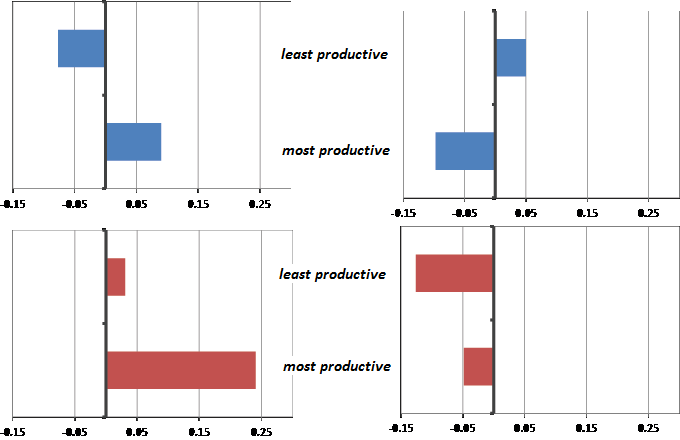

This is not all. The authors also publish figure 2 (their figure 5). According to them, more ‘structural reforms’ are needed to enable larger flows of labour from low productivity companies to high productivity companies to boost growth as well as adaptability of the economy. They are pretty confident this is happening: “Using simple joint distributions between firms’ productivity and selected covariates, we show that for stressed EU countries there is evidence that credit and labour is actually being reallocated towards the most productive use following the crisis. This would be in line with the postulate that the crisis and ensuing structural policies may be generating ‘cleansing effects“. In reality, the graph shows that the crisis – and not structural rigidity – is the real problem. During the upswing ‘rigidities’ did not (NOT) prevent a massive reallocation of labour to more productive companies, especially in the stressed countries. After 2008, ‘following the crisis’, the opposite (!) happened in the non-stressed countries. Also, implicitly calling the increase of unemployment caused by the shedding of labour by productive as well as less productive companies in the stressed countries a ‘reallocation of labour towards the most productive uses’ is pretty shocking. And not really sharp, when I think of it. Structural reforms failed – the wrong cure for the problem, based upon a flawed diagnosis and a severely lacking model of the patient. Calling what happened in the stressed economies ‘cleansing effects’ does not improve this situation.

Figure 2. Percentage change in total labour for firms above/below labour productivity median, for ‘stressed’ (red) and non-stressed (blue) countries. Left: before 2008. Right: after 2008.

What’s inside the neoliberal mind? Part 2 – Marketfundamentalist Marxism, kind of

March 28, 2015Leave a commentGo to comments

The latest ECB Economic Bulletin states: “In Portugal, the 2009-13 reforms have already raised the levels of productivity and potential GDP. According to OECD estimates the reforms will have resulted in a 3.5% increase in these variables by 2020″. This quote, from an article titled “Progress with structural reforms across the euro area and their possible impacts”, reminds one of the 1947 Isaac Asimov story about the endochronic nature of thiotimoline, the compound which “will dissolve before the water is added“. I mean – is it 2020 already?

The article is profoundly researched when it comes to neoclassical models – but lacks a proper diagnosis of the present situation and totally ignores even ECB papers which, when looking at the present day situation in the Eurozone in a serious way, produce results which makes the neoclassical view of events crumble. This recent high quality paper shows that government payment delays and arrears lead to increased levels of bankruptcy – another cost of bankruptcy and, as it shows that money matters, another blow to the idea of Ricardian equivalence. Still, government expenditure is strangely absent from the article. Or this recent ‘flow of funds’ analysis, which tries to establish a kind of national cash flow/debt analysis. Still, debts, the financial system and debt deflation are strangely absent from the article Or this recent one, which shows that the confidence fairy does not exist. Still, reforms are defined as confidence boosting by default. Or this recent one, about the (diminishing) differences between USA and Euro Area geographical labour mobility. Still, reforms of labour markets are seen as a panacea. The article is clearly profoundly underresearched when it comes to non-neoclassical ways of investigating the economy.

Oddly, it is even possible to read it as a tract from an unreformed Marxist economist earning his money by ghostwriting for a capitalist bank: class struggle, surplus value, a rigid division of classes into labourers on one side and capital owners on the other side, the declining rate of profit (and what to do about it) and a kind of labour theory of value – it’s all there. A little more on this below. First however the glaring lack of any kind of serious diagnosis of the present Eurozone problems – we might have a problem with aggregate demand (graph 1). Or high government and household debt. Or government austerity.

A low rate of investments does not necessarily mean that we have to boost investment. Maybe we have just moved to another epoch, characterized by a smaller flow of investment spending. But that does leave a hole in spending. Germany and the Netherlands succeeded in filling this spending hole (which started to increase since about 1970!) with exports, all countries increased government consumption and some countries filled it with increased consumer spending. Just stating, as the article does, that lower wages will increase confidence and will lead to a rebound of investment without giving any kind of serious thought to these kind o f problems does not do the trick – a valid cure can only be based on a valid diagnosis. But investigations like this one are absent. It really provides a micro cure for a macro disease.

Considering the almost Marxist stance of the article: phrases like the make one think of class struggle (in the Marxian labour-capitalist sense) and surplus value (mind that a wat mark-up is considered to be bad while a higher profit margin is, by definition, good):

Labour market reforms, to the extent that they reduce the wage mark-up or the reservation wage, should have a wage-moderating effect, which is reflected in improved competitiveness and/or higher profit margins for firms … because the initial wage-moderating effect of labour market reforms is reflected in a higher profit margin, firms have additional funds to invest and a higher return to capital…

This clearly is a classical Marxist labour-capital class struggle setting (again: Marxist classes are not something like ‘the middle class’ or even the ‘0,1%’ but ‘labour’ and ‘capital’). It won’t come as a surprise that lower wages and employment will, according to the article, lead to higher confidence and investments (in the long run). In that sense, it can, on a meta-level, also be understood as part of the ‘superstructure’ of society. And though macro Unit Labour Costs are not central to the article, they are mentioned – and indeed used as a kind of labour theory of value…

The real problem is however that the article totally ignores cyclical unemployment, government expenditure, financial and housing bubbles, the decline in investment and comparable events. While, as everybody is assumed to behave in the way neoclassical economists want us to behave, reforms will not just lead to higher unemployment and lower wages but will also boost confidence and investments which, as stated, is not what happens. As such aspects are ignored they also can’t be part of the diagnosis – or even the cure. The solutions are consistent on their own terms. Consistent… but wrong.

Caveat: Portugal, Greece and Spain did not show sign of stagnation before 2008, which means that, yes, there were serious problems but lack of dynamism wasn’t one of them. Italy, however, did show these signs (multiple no growth decades (the economic consequences of mr. Berlusconi?), an extra-ordinary high difference between broad and normal unemployment). Which means that there may (!) be good reasons to accept that the Italian economy does need reinvigoration – and end to the mafia and ‘Berlusconi’ (both pretty succesful market oriented entities, by the way). The point: such an analysis is totally absent from the article – a proper diagnosis is lacking.