Yes, there are many alternatives to rentier capitalism. This is one.

from PBS newshour (more on the original website)

When Canadian journalist and friend of Making Sense Frank Koller published his book “Spark”, about the profit-sharing model pioneered at Cleveland’s Lincoln Electric, it encouraged Making Sense to return to the manufacturer after first reporting on them back in 1992. You can watch our update from 2011 above. (And here is a response to those who thought we were too easy on Lincoln.) Two years later, Koller now updates us on yet another profitable year for Lincoln.

Frank Koller: The annual profit-sharing bonus ceremony was held Friday in Lincoln Electric’s Cleveland cafeteria, which Making Sen$e has covered extensively over the years on the NewsHour and on the Business Desk. Here are the latest numbers for the Ohio-based multinational welding manufacturer, now 118 years old:

80: uninterrupted years of paying an employee bonus (i.e. profitable every year since 1934)

$33,029: average 2013 bonus per U.S. employee (roughly 3,000 employees)

$81,366: average 2013 total earnings per U.S. employee (wages or salary + bonus)

$100.7 million: total pre-tax profit shared with employees, Lincoln’s largest bonus pool ever

0: number of layoffs in 2013 (that makes 65 years without any layoffs)

#1: Lincoln Electric remains number one in the global marketplace in its industry. (As “LECO” on the Nasdaq exchange, its stock is currently at an all-time high.)

The difference a price level makes

The European Central Bank targets the consumer price level, among other reasons because neoclassical macro-economic models often picture a world where this is the only level which matters. Indeed, as there is only one product in quite some models, the only level which even can exist. In reality, money is not only used to purchase vegetables and cars (household consumption) but also to pay for street lights (government consumption)and new houses and machinery (fixed investment). Theoretically, a broader inflation metric like ‘domestic demand inflation’ (household consumption + government consumption + investments) is therefore superior to a consumption price metric as far as targets go.

In a practical sense, this wold not matter too much if all metrics showed the same medium term developments. But they don’t. One of the causes of the Euro crisis are differences in the rate of, especially, asset price inflation, including the price of land which shows up in the price of investments in new houses and buildings. This holds too when we compare domesticdemand prices with core prices, i.e. consumption prices without energy. And these investment prices show up in the price level of total domestic demand. When we look at differences in changes in the domestic demand price level it shows that these are much larger than changes in the consumer price level. Notice that in Germany the domestic demand price level increased less than consumption prices while the opposite was the case in Spain.

Looking at the price level of domestic demand instead of the consumer price level, in combination with a theory of the relation between asset price rises, finance and bubbles(Minskyian or Austrian, doesn’t matter) would have shown a much faster increase of imbalances than just looking at consumer prices. Let me be clear on this: for years in a stretch higher inflation in Spain attrackted money, instead of leading to lower expenditure – which is not really what the neoclassical models state.

As an alternative to consumption price inflation the GDP deflator is often used, which is even broader based than domestic demand inflation. This metric is however influenced by the terms of trade of a country, i.e. by the exchange rate, which makes it less fit (to say the least) as a policy target.

Micro foundations: help! Help! HELP!

Can anybody explain to me how an intelligent, perfectly reasonable economist can write this(emphasis added):

Let’s take a very basic example. Suppose in the real world some consumers arecredit constrained, while others are infinitely lived intertemporal optimisers.

And can anybody explain to this intelligent, perfectly reasonable man that, in the real real world, a population can not be described by (quote) micro theory about how individuals may behave. It’s not just that (as every, and I mean every marketeer who actually tries to sell something knows) neoclassical micro theory does not tell us anything meaningful about actual behaviour of people. As this can not be explained by rational ‘choices’ as, for one thing, preferences are not time and situation consistent. But a population also does not act like an individual, the representative heshe consumer does not exist.

Though this omnipotent all-knowing individual is of course a useful artefact to neglect differences between people, like ‘employed/unemployed’, ‘house owner/renter’, ‘rich/poor’, ‘have/have not’ etcetera. Etcetera. The representative consumer lives forever in a representative house which it/he/she partly owns and partly rents (from it/him/herself). Forever. Mindboggling.

from Lars Syll

There is something about the way macroeconomists construct their models nowadays thatobviously doesn’t sit right.

Empirical evidence only plays a minor role in neoclassical mainstream economic theory, where models largely function as a substitute for empirical evidence.

One might have hoped that humbled by the manifest failure of its theoretical pretences during the latest economic-financial crisis, the one-sided, almost religious, insistence on axiomatic-deductivist modeling as the only scientific activity worthy of pursuing in economics would give way to methodological pluralism based on ontological considerations rather than formalistic tractability. That has, so far, not happened.

Fortunately — when you’ve got tired of the kind of macroeconomic apologetics produced by “New Keynesian” macroeconomists and other DSGE modellers — there still are some real Keynesian macroeconomists to read. One of them – Axel Leijonhufvud – writes:

For many years now, the main alternative to Real Business Cycle Theory has been a somewhat loose cluster of models given the label of New Keynesian theory. New Keynesians adhere on the whole to the same DSGE modeling technology as RBC macroeconomists but differ in the extent to which they emphasise inflexibilities of prices or other contract terms as sources of shortterm adjustment problems in the economy. The “New Keynesian” label refers back to the “rigid wages” brand of Keynesian theory of 40 or 50 years ago. Except for this stress on inflexibilities this brand of contemporary macroeconomic theory has basically nothing Keynesian about it …

I conclude that dynamic stochastic general equilibrium theory has shown itself an intellectually bankrupt enterprise. But this does not mean that we should revert to the old Keynesian theory that preceded it (or adopt the New Keynesian theory that has tried to compete with it). What we need to learn from Keynes … are about how to view our responsibilities and how to approach our subject.

If macroeconomic models – no matter of what ilk – build on microfoundational assumptions of representative actors, rational expectations, market clearing and equilibrium, and we know that real people and markets cannot be expected to obey these assumptions, the warrants for supposing that conclusions or hypotheses of causally relevant mechanisms or regularities can be bridged, are obviously non-justifiable. Incompatibility between actual behaviour and the behaviour in macroeconomic models building on representative actors and rational expectations microfoundations is not a symptom of “irrationality”. It rather shows the futility of trying to represent real-world target systems with models flagrantly at odds with reality.

A gadget is just a gadget – and no matter how brilliantly silly DSGE models you come up with, they do not help us working with the fundamental issues of modern economies. Using DSGE models only confirms Robert Gordon‘s dictum that today

rigor competes with relevance in macroeconomic and monetary theory, and in some lines of development macro and monetary theorists, like many of their colleagues in micro theory, seem to consider relevance to be more or less irrelevant.

The microfundationalist illusions of Yates and Wren-Lewis

from Lars Syll

In a blogpost the other day Tony Yates argues that microfoundations do have merits:

The merit in any economic thinking or knowledge must lie in it at some point producing an insight, a prediction, a prediction of the consequence of a policy action, that helps someone, or a government, or a society to make their lives better.

Microfounded models are models which tell an explicit story about what the people, firms, and large agents in a model do, and why. What do they want to achieve, what constraints do they face in going about it? My own position is that these are the ONLY models that have anything genuinely economic to say about anything.

And yesterday Simon Wren-Lewis — non-surprisingly — says he basically agrees:

microfoundations have done a great deal to advance macroeconomics. It is a progressive research program, and a natural way for macroeconomic theory to develop. That is why I work with DSGE models.

microfoundations have done a great deal to advance macroeconomics. It is a progressive research program, and a natural way for macroeconomic theory to develop. That is why I work with DSGE models.

The one economist/econometrician/methodologist who has thought most on this issue — writing om microfoundations for now more than 25 years — is without any doubts Kevin Hoover. It’s actually quite interesting to compare his qualified and methodologically founded assessment on the representative-agent-rational-expectations microfoundationalist program with the more or less apologetic views of Yates and Wren-Lewis:

Given what we know about representative-agent models, there is not the slightest reason for us to think that the conditions under which they should work are fulfilled. The claim that representative-agent models provide microfundations succeeds only when we steadfastly avoid the fact that representative-agent models are just as aggregative as old-fashioned Keynesian macroeconometric models. They do not solve the problem of aggregation; rather they assume that it can be ignored. While they appear to use the mathematics of microeconomis, the subjects to which they apply that microeconomics are aggregates that do not belong to any agent. There is no agent who maximizes a utility function that represents the whole economy subject to a budget constraint that takes GDP as its limiting quantity. This is the simulacrum of microeconomics, not the genuine article …

Given what we know about representative-agent models, there is not the slightest reason for us to think that the conditions under which they should work are fulfilled. The claim that representative-agent models provide microfundations succeeds only when we steadfastly avoid the fact that representative-agent models are just as aggregative as old-fashioned Keynesian macroeconometric models. They do not solve the problem of aggregation; rather they assume that it can be ignored. While they appear to use the mathematics of microeconomis, the subjects to which they apply that microeconomics are aggregates that do not belong to any agent. There is no agent who maximizes a utility function that represents the whole economy subject to a budget constraint that takes GDP as its limiting quantity. This is the simulacrum of microeconomics, not the genuine article …

[W]e should conclude that what happens to the microeconomy is relevant to the macroeconomy but that macroeconomics has its own modes of analysis … [I]t is almost certain that macroeconomics cannot be euthanized or eliminated. It shall remain necessary for the serious economist to switch back and forth between microeconomics and a relatively autonomous macroeconomics depending upon the problem in hand.

So next time these guys want to write atrocities like Wren-Lewis’s

Let’s take a very basic example. Suppose in the real world some consumers are credit constrained, while others are infinitely lived intertemporal optimisers. A microfoundation modeller assumes that all consumers are the latter

a visit to Dr Hoover is recommended!

Real World Economics Data Archive on Decline of the USA internally and globally: http://rwer.wordpress.com/category/decline-of-the-usa/

Archive for the ‘Decline of the USA’ Category

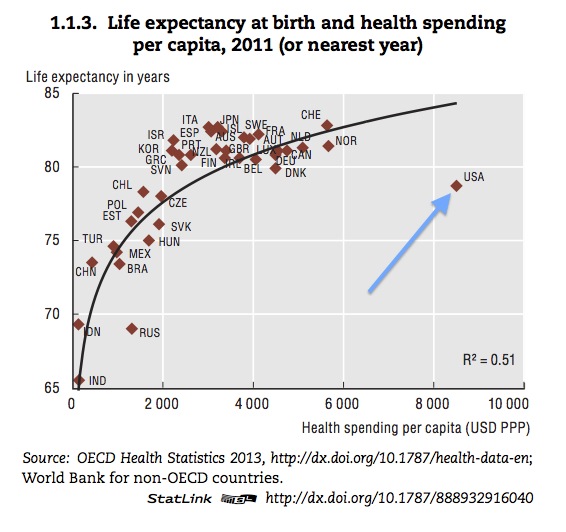

39 country chart of life expectancy and health spending per captia

Horns of a dilemma

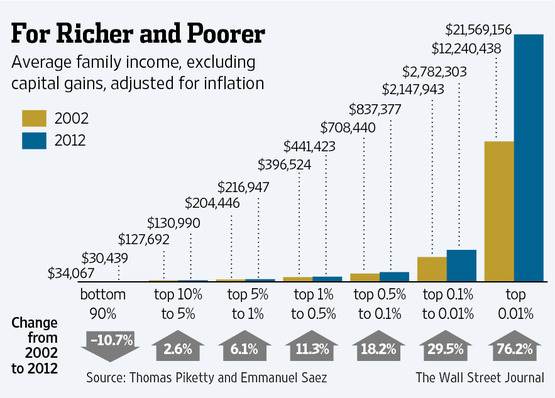

from David Ruccio

The Wall Street Journal notes that rising inequality may pose a problem—because of issues like fairness, political dysfunction, and financial instability. Read more…

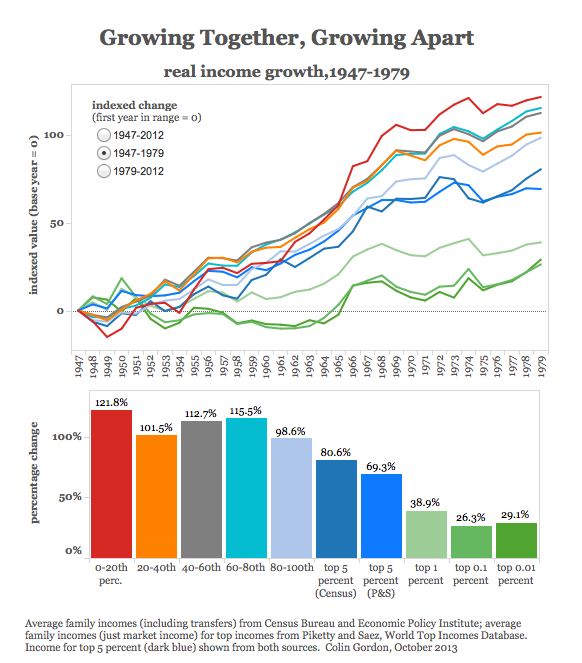

Two American epochs: Growing Together 1947-1979 and Growing Apart 1979-2012 (charts)

from David Ruccio

The Lucas Mystique

from Peter Radford

There is this thing in economics called the Lucas Critique. You see it pop up every so often and hear it referred to in revered tones. It is, apparently, very important and very, very, insightful. It has a lot to do with the state of economics today. Which, as you know, I think of as being lamentable.

What is this Critique?

Well, in a nutshell, it says that there are special features of an economy that are “deep”, by which it means they don’t move about in the face of policy changes. Other features, presumably the “shallow” ones do. This is important because it implies that policy makershave to be sure that the things they are trying to influence don’t slip and slide about too much in reaction to their policies and, in effect, neutralize those policies. In short: Lucas says people take policy into account, make suitable adjustments, and thus render some – if not all – policies ineffective.

Not quite. The only policies that are ineffective are those that are based on those “shallow” features. Which, it turns out, happens to be pretty much anything Keynesian.

Why?

Because Keynes focused on macro effects and dealt with large scale or aggregate features of the economy. Things like aggregate demand for instance. He didn’t spend much time mucking around with the behaviors of individual people of businesses. Or, at least, he felt comfortable dealing with aggregates and presumed they had analytical validity. Lucas argued that such aggregates are not “deep” because they do not take into account the possible adjustments made by people and firms when confronted by policy changes.

To get around this problem Lucas and his followers urged economists to rebuild their models of the economy – the ones used for policy advice – on the more substantial “deep” features that offered a more concrete basis for analysis. Since these were presumed to be those features theorized about within what is called microeconomics, new models of the economy, and therefore macroeconomics, had to henceforth be built on what is nowadays called a “micro-foundation”.

How nice.

Or at least it would be were those micro foundations worth a lick. Which they aren’t. They are absurd. What the Lucas Critique effectively reduced economics to was a combination of applied math built on top of the results of what is a kind of psychology. Bad psychology. Other worldly psychology. Economists who operate within the confines set by the Lucas Critique build huge model superstructures on the decidedly sandy foundations of nutty and wholly unrealistic views of how people act.

Since real people tend to be a little idiosyncratic, odd, and sometimes unreliable, and since it is difficult to model such traits, economists swept them under the carpet and hypothesized something altogether different. That something being easier to fit into mathematical models and thus manipulate.

Since economists find it easier to model rational behavior, people became rational in the models. And not just rational in the manner of being sensible, but hyper rational in the manner of being an automaton.

Since people sometimes differ even when they’re being rational, economists decided to use only one – a “representative” – in their models. They did the same for businesses. Not only this, they decided that all the goods and services in the economy – hair cuts and motor cars – are substitutes for each other. This helps get around the knotty problem of what people do when they make decisions on what to spend they money on. Not that economists allow them to change their minds in the models. And not that money is ever really built in either. Getting rid of money was quite a coup because it meant economists didn’t have to worry about why people might not spend everything they earned. Instead economists could simply focus on a moneyless economy and study “real” things like widgets and corn bushels. You know, the stuff we all buy.

These micro-founded models are the ones that failed to predict the crash. No wonder. They are “deep”. So deep they are lost in the mud at the bottom of a very deep and opaque analytical imaginary world where the light of the real world never penetrates.

Nonetheless the Critique stands proudly as a totem of great insight.

It provides cover for those who want to deny the real world. Those who deny that the whole is greater than the sum of its parts. Those who deny that properties emerge at various levels of aggregation and are not thus based on anything below them. Those who prefer to deny that humans are diverse and complicated. Those who prefer to limit themselves the very special circumstances of the highly unlikely possibility of an equilibrium. Those who are desperate to laud market magic as the panacea to all that ails an economy. And those who, for some unimaginable reason, seem to think that modern economics has something useful to say about a society’s ability to accrue and distribute wealth.

The Critique is not a critique. It is a mystery. A Mystique. Another of a line of great sounding insights that melt into commonsensical vapor when probed. Of course we ought to take people into account when we model an economy. Of course their reactions to policy matter. Duh. Only an economist would think this is an insight worthy of having a special name.

Lucas gave his critique in the context of his program to introduce rational expectations into economics., but his critique does not depend on rationality. It depends simply on the observation that people have expectations and adjust them when the suite of facts they face changes. Wow. People change their minds periodically. Who knew?

Economics has endured an epic decades long journey into irrelevance partially instigated by the Lucas Critique, and the paraphernalia of the micro-foundations it elevated to canonical status. Meanwhile Keynesian analysis has reemerged as the relevant focal point for policies that actually solve problems.

Lucas lost. Critique and all.

Now, if only we could get people to understand that “market clearing” and “equilibrium” are not the same thing. But that’s another topic.