Plutonomy and its 12-point manifesto

June 2, 2014Leave a commentGo to comments

from Edward Fullbrook

This appeared on my screen last night.

The Plutonomist Manifesto

- Because democracy is our worst enemy, we must work to convert every democracy in the world to a fake democracy.

- We, The One-percent, achieve these conversions of the system of government through three forms of targeted ownership.

a. Owning mass media, the internet and the Web.

b. Owning all major political parties. We achieve this ownership by making the electoral process extremely expensive, thereby making election dependent on our financial support.

c. Owning economists. In today’s world the economics profession determines what the electorate sees and does not see regarding the economy. Therefore it is imperative that we control it. We achieve this by maintaining remunerative revolving doors, by financing think tanks and university economics departments, by funding Trojan Horse organizations to co-opt non-One-percent economists, and by our Nobel Prize.- In countries with real democratic traditions, plutonomy revolutions are achievable only by using Trojan Horse Methods (THMs). Subversion rather than violence or open campaigning is our means of conquest.

- The use of THMs means that sometimes we must be seen to give support to our opponents.

- We must be vigilant against leakages (for example, the Citigroup documents) of the existence of our program.

- When approached always give lip-service in support of democracy.

- The middleclass is both our means to success and our ultimate obstacle. It is they, not the poor, who have what we want. Hence the necessity of THMs.

- Ridicule all suggestions of our existence as the work of conspiracy theorists, and label people who support middleclass interests over ours as “leftists”.

- Channel funds to the emerging neo-fascists parties in the US and EU countries because their shenanigans camouflage our redistributions.

- We must work to expand and refine our armoury of redistribution mechanisms.

- The success we have had in the USA and the UK in redistributing middle-class income and wealth to ourselves must now in the next 15 years be duplicated across Western Europe, most especially in France and Germany.

- Our goal of receiving forty percent of income and owning 80 percent of wealth is achievable in most countries of the world my mid-century.

REDISTRIBUTION – REDISTRIBUTION – REDISTRIBUTION

This and this explain the reference in #5 to “Citigroup documents”.

Citigroup Plutonomy Report:

Citigroup-Plutonomy-Report-Part-1

Citigroup_Plutonomy_Report_Part_2

citibank plutonomy symposium memo3

Neoclassical-Economics-and-Neoliberalism-as-Neo-Imperialism-2 (1)

All inequality all the time

from David Ruccio

It’s clear we are in the midst of an acute period of inequality: not only of grotesque levels of economic inequality (which are now well documented) but also of a wide-ranging discussion of the conditions and consequences of that extreme inequality (which appears to be taking off).

There are, of course, the deniers, like my dear friend Deirdre McCloskey. What inequality, is her mantra. The only thing that matters is economic growth, such that the amount of stuff people have today is much more than they’ve had throughout much of human history. OK, but that doesn’t tell us much about how that growth took place (it’s the surplus, Deirdre) or what it’s consequences are (on the majority who actually produce the surplus versus the tiny minority who appropriate it).

And then there are those who are actually thinking seriously about inequality, some of whose work is published in the latest issue of Science (a lot of which, unfortunately, is behind a paywall). Leave aside the silly article on econophysics (really, the existing distribution of income is a kind of “natural inequality,” which is what you would get from entropy?), the article that focuses on the psychological pathologies of the poor (what about those of the rich?), and the fact that all the economics is narrowly confined to mainstream theories (which have done more to deflect attention from, as against the wide range of heterodox theories that have actually focused on, inequality over the course of the past three decades). Just the fact that a special issue of such a prestigious journal is devoted to the problem of inequality tells us something about how it has risen to the top of our agenda.

And it offers lots here to think about: the types of inequality that can be found in the archeological record (Heather Pringle), the absence of fundamental inequalities in hunter-gatherer societies (Elizabeth Pennisi), the devastating effects of inequality on health (Emily Underwood), growing inequality in developing countries (Mara Hvistendahl and Martin Ravallion), the intergenerational transmission of inequality via unequal maternal circumstances and health at birth ( and Janet Currie), and finally a dire warning about what will happen if current inequalities continue to grow (Angus Deaton):

The distribution of wealth is more unequal than the distribution of income, and very high incomes will eventually pupate into very large fortunes, ultimately leading to a hereditary dystopia of idle rich.

The pair of articles by economists—one by Thomas Piketty and Emmanuel Saez, the other by David Autor—tells us a great deal about how the issue of inequality is being framed within mainstream economics (since, as I wrote above, all the various types of nonmainstream economics are simply ignored in the issue). For Piketty and Saez, it’s all about the inequality (both income and wealth) that separates the top 1 percent (and, within that, the top .1 percent and .01 percent) from everyone else, while Autor’s piece focuses on the inequality of earnings within the bottom 99 percent. The debate comes down to seeing inequality as a result of high CEO incomes and returns on accumulated wealth (especially when the rate of return on wealth is greater than the overall growth rate, leading to more concentration of wealth) versus the inequality that derives from earnings based on different levels and kinds of skill (presuming that earnings are equal to marginal productivities). In other words, it’s a (mostly) classical approach—which focuses on scarce wealth concentrated in the hands of the already rich—versus a (thoroughly) neoclassical approach—according to which scarce skills attract higher earnings. The solution from the classical perspective is a global tax on wealth; from the neoclassical viewpoint, all we need is an increase in education and skills for those at the bottom.

Here’s what I find interesting about the debate, not only between the economists but throughout the entire special issue: it’s all about economic inequality—what it is (absolute or relative), how it can be measured (within and across nations, and over time), what its causes and consequences are (including not only the health of individuals but also of society as a whole), and so on—but there’s not a single mention of class.

Not literally. The word class doesn’t appear in any of the articles or reviews. But class is the specter that, in my view, haunts this entire debate. We saw it back in the First Great Depression. And now we’re seeing it rear its ugly head once again, in the midst of the Second Great Depression. We didn’t solve it then. Perhaps, now, we’re ready to tackle it.

And, if we don’t, we’ll be faced with even more inequality all the time.

Update

As if on cue, the latest issue of the American Spectator focuses on what they consider to be the “new class warfare”—using as a threat the universal symbol of “off with their heads.”

For which Gavin Mueller offers the only appropriate response:

Remember this: no matter how many country clubbers flip through Piketty’s book, at bottom, the rich hate us. They disdain us. They mock us. And they fear us, even though the current balance of forces favors them overwhelmingly and sometimes “common ruin of the contending classes” seems like an optimistic outcome.

Yet I have to fall back on some advice I got as a kid: If the American Spectator wants to cry about class warfare, we should give them something to cry about.

Nonlinearities of the sabotage-redistribution process (5 graphs)

from Shimshon Bichler and Jonathan Nitzan

A recent exchange on capitalaspower.com, titled ‘Capitalizing Time’, suggests a possible confusion regarding our claims, so a clarification is in order. Over the years, we have argued that the relationship between sabotage and distribution tends to be nonlinear. Up to a point, sabotage redistributes income in favour of those who impose it; but after that point, sabotage becomes ‘excessive’ and the effect inverts. One illustration of this nonlinearity is given by the relationship between unemployment and the capital share of income.

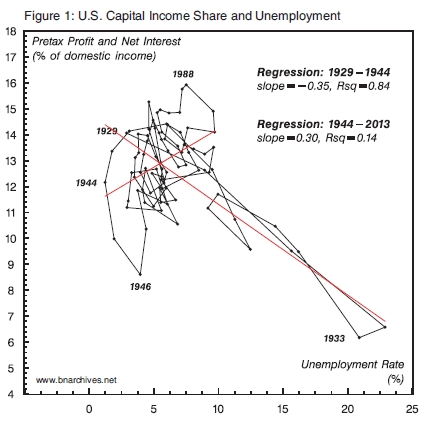

In ‘Capitalizing Time’, Blair Fix plots this relationship, with the income share of capitalists on the vertical axis and the rate of unemployment on the horizontal axis. However, the low-pixel graphics of the chart are too crude to reveal the nonlinearity. Figure 1 corrects this shortcoming. It shows the same relationship, but with finer graphics that make the nonlinearity visible (the definitions and sources for all figures are given in the Appendix). Note that, unlike Blair, we use the capital share of domestic income rather than of national income. The reason is that the latter measure includes foreign profit and interest, which are unaffected by domestic unemployment. In practice, though, the two sets of data yield similar results.

Now, if we treat the entire 1929-2013 period as representing a single pattern, the relationship is negative. But we can also think of this history as representing two very different regimes, separated by what econometricians call ‘structural change’: (1) the prewar period (16 years), when sabotage was excessive and unemployment undermined the capitalist share of income (regression slope = –0.35); and (2) the postwar era (70 years), when, following a structural change, sabotage has become strategic and unemployment has boosted the share of capital (regression slope = +0.3).

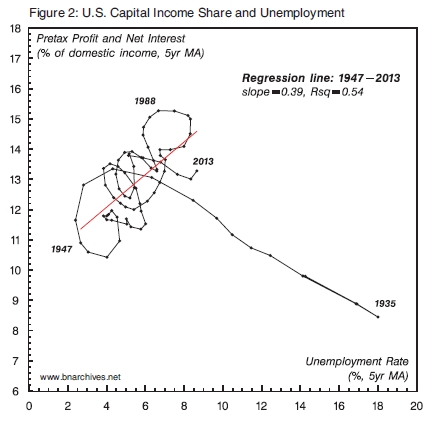

To see the nonlinearity more clearly, Figure 2 smoothes the two variables as 5-year moving averages. The difference between the two regimes is now easier to discern. The negative prewar relationship is almost linear, while the positive postwar relationship is tighter than the one shown with the unsmoothed data. This relationship, using national income data, was first plotted in our paper ‘Capital Accumulation: Breaking the Dualism of “Economics” and “Politics”’(Nitzan and Bichler 2000: Figure 5.2, p. 80) and later updated in various publications.

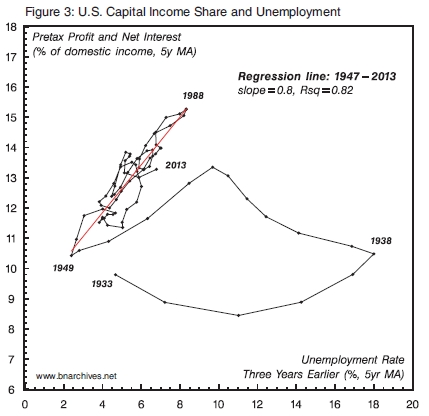

Figure 3 takes the analysis a step further by showing the relationship between the income share of capital and the rate of unemployment three year earlier (with both series still expressed as 5-year moving averages). The same relationship – though without the prewar data – was shown in Figures 15 and 16 of our paper ‘Can Capitalists Afford Recovery: Economic Policy When Capital is Power’ (Bichler and Nitzan 2013).

All three figures indicate a nonlinearity; this nonlinearity becomes clearer as we smooth the data; and the positive effect of strategic sabotage in the postwar period grows much tighter when we use unemployment with a three-year lag. These regularities suggest that strategic sabotage takes time to creorder the distribution of income. In principle, one can estimate this process with a distributed-lag regression, with the capital income share as the variable of interest and lagged values of unemployment as carriers; unfortunately, though, the high multicollinearity of the carriers will likely prevent us from assessing their distinct impacts.

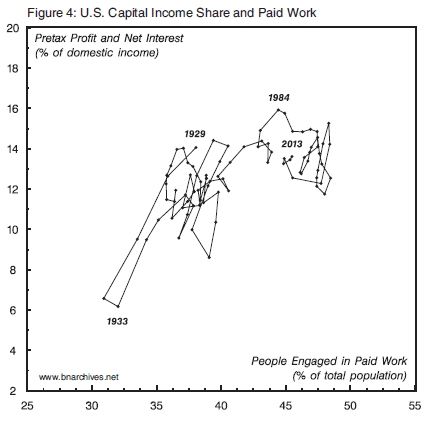

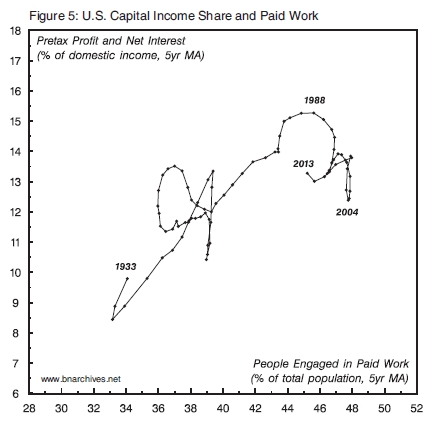

Figure 4 shows Blair’s original relationship between the capital share of income (which, here too, we measure as a proportion of domestic rather than national income) and the per cent of the population engaged in paid work. To enable comparison with the previous three charts, we switch Blair’s axes, putting the capital share of income on the vertical axis and the proportion of paid workers on the horizontal one.

Our interpretation of this relationship is that the proportion of the population in paid work reflects the ability of capitalists to force people into the capitalization process, and that this process is a manifestation of capitalist power. But the effect of this power is nonlinear as well: beyond a certain point the underlying sabotage becomes ‘excessive’, the relationship experiences a ‘structural change’ and the impact on the capitalist share of income inverts. In the United States, this inversion appears to have happened after 1984: as the proportion of the population in paid work rose beyond 45 per cent, the income share of capital started to drop. Figure 5 smoothes both variables as 5-year moving averages, yielding a sharper picture of this nonlinearity.

Appendix: Definitions and Sources

Domestic income. Source: U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis through Global Insight (series codes: GDY).

Domestic net interest. Source: U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis through Global Insight (series codes: INTNETDBUS).

Domestic profit. Reported pretax and includes capital consumption adjustment (CCAdj) and inventory valuation adjustment (IVA). Source: U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis through Global Insight (series codes: ZBECOND).

Population. Source: Historical Statistics of the United States: Earliest Times to the Present, Millennial Edition (online) (series code: Aa7 [till 1929]); U.S. Bureau of the Census through Global Insight (series code: N@US [from 1930 onward]).

Unemployment. Expressed as a share of the labour force. Source: Historical Statistics of the United States, Earliest Times to the Present: Millennial Edition (online) (series code: Unemployed_AsPercentageOf_CivilianLaborForce_Ba475_Percent [till 1947]); U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics through Global Insight (series code: RUC, computed as annual averages of monthly data [1948 onward]).

Endnotes

[1]Shimshon Bichler teaches political economy at colleges and universities in Israel. Jonathan Nitzan teaches political economy at York University in Canada. All of their publications are available for free on The Bichler & Nitzan Archives (http://bnarchives.net). Research for this paper was partly supported by the SSHRC.

References

Bichler, Shimshon, and Jonathan Nitzan. 2013. Can Capitalists Afford Recovery? Economic Policy When Capital is Power. Working Papers on Capital as Power (2013/01, October): 1-36.

Nitzan, Jonathan, and Shimshon Bichler. 2000. Capital Accumulation: Breaking the Dualism of “Economics” and “Politics”. In Global Political Economy: Contemporary Theories, edited by R. Palan. New York and London: Routledge, pp. 67-88.

By totally avoiding the issue of inequality in the distribution of wealth and income, these models often lead to extreme and unrealistic conclusions and are therefore a source of confusion rather than clarity. In the case of public debt, representative agent models can lead to the conclusion that government debt is completely neutral, in regard not only to the total amount of national capital but also to the distribution of the fiscal burden. This radical reinterpretation of Ricardian equivalence … fails to take account of the fact that the bulk of public debt is in practice owned by a minority of the population … so that the debt is the vehicle of important internal redistributions when it is repaid as well

By totally avoiding the issue of inequality in the distribution of wealth and income, these models often lead to extreme and unrealistic conclusions and are therefore a source of confusion rather than clarity. In the case of public debt, representative agent models can lead to the conclusion that government debt is completely neutral, in regard not only to the total amount of national capital but also to the distribution of the fiscal burden. This radical reinterpretation of Ricardian equivalence … fails to take account of the fact that the bulk of public debt is in practice owned by a minority of the population … so that the debt is the vehicle of important internal redistributions when it is repaid as well