KISSINGER AND CHILE: THE DECLASSIFIED RECORDKissinger pressed Nixon to overthrow the democratically elected Allende government because his “‘model’ effect can be insidious,” documents showOn 40th anniversary of coup, Archive posts top ten documents on Kissinger’s role in undermining democracy, supporting military dictatorship in ChileKissinger overruled aides on military regime’s human rights atrocities; told Pinochet in 1976: “We want to help, not undermine you. You did a great service to the West in overthrowing Allende.”National Security Archive Electronic Briefing Book No. 437Posted – September 11, 2013 Edited by Peter Kornbluh For more information contact:

|

Washington, D.C., September 11, 2013 – Henry Kissinger urged President Richard Nixon to overthrow the democratically elected Allende government in Chile because his “‘model’ effect can be insidious,” according to documents posted today by the National Security Archive. The coup against Allende occurred on this date 40 years ago. The posted records spotlight Kissinger’s role as the principal policy architect of U.S. efforts to oust the Chilean leader, and assist in the consolidation of the Pinochet dictatorship in Chile.

Archive. The coup against Allende occurred on this date 40 years ago. The posted records spotlight Kissinger’s role as the principal policy architect of U.S. efforts to oust the Chilean leader, and assist in the consolidation of the Pinochet dictatorship in Chile.

The documents, which include transcripts of Kissinger’s “telcons” — telephone conversations — that were never shown to the special Senate Committee chaired by Senator Frank Church in the mid 1970s, provide key details about the arguments, decisions, and operations Kissinger made and supervised during his tenure as national security adviser and secretary of state.

adviser and secretary of state.

“These documents provide the verdict of history on Kissinger’s singular contribution to the denouement of democracy and rise of dictatorship in Chile,” said Peter Kornbluh who directs the Chile Documentation Project at the National Security Archive. “They are the evidence of his accountability for the events of forty years ago.”

Archive. “They are the evidence of his accountability for the events of forty years ago.”

Today’s posting includes a Kissinger “telcon” with Nixon that records their first conversation after the coup. During the conversation Kissinger tells Nixon that the U.S. had “helped” the coup. “[Word omitted] created the conditions as best as possible.” When Nixon complained about the “liberal crap” in the media about Allende’s overthrow, Kissinger advised him: “In the Eisenhower period, we would be heroes.”

That “telcon” is published for the first time in the newly revised edition of Kornbluh’s book,The Pinochet File: A Declassified Dossier on Atrocity and Accountability, (The New Press, 2013), which has been re-released for the 40th anniversary of the coup. Several of the other documents posted today appeared for the first time in the original edition, which the Los Angeles Times listed as a “Best Book” of 2003.

Among the key revelations in the documents:

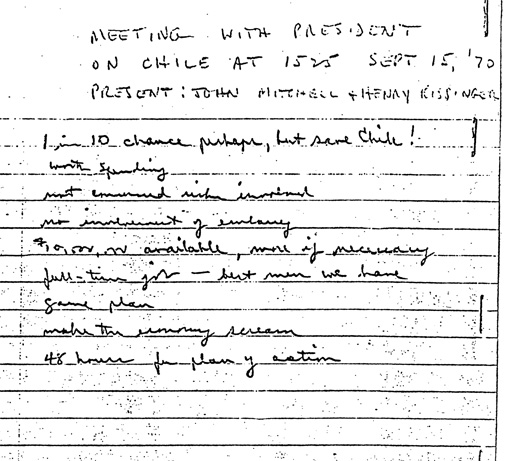

- On September 12, eight days after Allende’s election, Kissinger initiated discussion on the telephone with CIA director Richard Helm’s about a preemptive coup in Chile. “We will not let Chile go down the drain,” Kissinger declared. “I am with you,” Helms responded. Their conversation took place three days before President Nixon, in a 15-minute meeting that included Kissinger, ordered the CIA to “make the economy scream,” and named Kissinger as the supervisor of the covert efforts to keep Allende from being inaugurated. Since the Kissinger/Helms “telcon” was not known to the Church Committee, the Senate report on U.S. intervention in Chile and subsequent histories date the initiation of U.S. efforts to sponsor regime change in Chile to the September 15 meeting.

- Kissinger ignored a recommendation from his top deputy on the NSC, Viron Vaky, who strongly advised against covert action to undermine Allende. On September 14, Vaky wrote a memo to Kissinger arguing that coup plotting would lead to “widespread violence and even insurrection.” He also argued that such a policy was immoral: “What we propose is patently a violation of our own principles and policy tenets .… If these principles have any meaning, we normally depart from them only to meet the gravest threat to us, e.g. to our survival. Is Allende a mortal threat to the U.S.? It is hard to argue this.”

- After U.S. covert operations, which led to the assassination of Chilean Commander in Chief of the Armed forces General Rene Schneider, failed to stop Allende’s inauguration on November 4, 1970, Kissinger lobbied President Nixon to reject the State Department’s recommendation that the U.S. seek a modus vivendi with Allende. In an eight-page secret briefing paper that provided Kissinger’s clearest rationale for regime change in Chile, he emphasized to Nixon that “the election of Allende as president of Chile poses for us one of the most serious challenges ever faced in this hemisphere” and “your decision as to what to do about it may be the most historic and difficult foreign affairs decision you will make this year.” Not only were a billion dollars of U.S. investments at stake, Kissinger reported, but what he called “the insidious model effect” of his democratic election. There was no way for the U.S. to deny Allende’s legitimacy, Kissinger noted, and if he succeeded in peacefully reallocating resources in Chile in a socialist direction, other countries might follow suit. “The example of a successful elected Marxist government in Chile would surely have an impact on — and even precedent value for — other parts of the world, especially in Italy; the imitative spread of similar phenomena elsewhere would in turn significantly affect the world balance and our own position in it.”The next day Nixon made it clear to the entire National Security

Council that the policy would be to bring Allende down. “Our main concern,” he stated, “is the prospect that he can consolidate himself and the picture projected to the world will be his success.”

Council that the policy would be to bring Allende down. “Our main concern,” he stated, “is the prospect that he can consolidate himself and the picture projected to the world will be his success.” - In the days following the coup, Kissinger ignored the concerns of his top State Department aides about the massive repression by the new military regime. He sent secret instructions to his ambassador to convey to Pinochet “our strongest desires to cooperate closely and establish firm basis for cordial and most constructive relationship.” When his assistant secretary of state for inter-American affairs asked him what to tell Congress about the reports of hundreds of people being killed in the days following the coup, he issued these instructions: “I think we should understand our policy-that however unpleasant they act, this government is better for us than Allende was.” The United States assisted the Pinochet regime in consolidating, through economic and military aide, diplomatic support and CIA assistance in creating Chile’s infamous secret police agency, DINA.

- At the height of Pinochet’s repression in 1975, Secretary Kissinger met with the Chilean foreign minister, Admiral Patricio Carvajal. Instead of taking the opportunity to press the military regime to improve its human rights record, Kissinger opened the meeting by disparaging his own staff for putting the issue of human rights on the agenda. “I read the briefing paper for this meeting and it was nothing but Human Rights,” he told Carvajal. “The State Department is made up of people who have a vocation for the ministry. Because there are not enough churches for them, they went into the Department of State.”

- As Secretary Kissinger prepared to meet General Augusto Pinochet in Santiago in June 1976, his top deputy for Latin America, William D. Rogers, advised him make human rights central to U.S.-Chilean relations and to press the dictator to “improve human rights practices.” Instead, a declassified transcript of their conversation reveals, Kissinger told Pinochet that his regime was a victim of leftist propaganda on human rights. “In the United States, as you know, we are sympathetic with what you are trying to do here,” Kissinger told Pinochet. “We want to help, not undermine you. You did a great service to the West in overthrowing Allende.”

At a special “Tribute to Justice” on September 9, 2013, in New York, Kornbluh received the Charles Horman Truth Foundation Award for the Archive’s work in obtaining the declassification of thousands of formerly secret documents on Chile after Pinochet’s arrest in London in October 1998. Other awardees included Spanish Judge Baltazar Garzon who had Pinochet detained in London; and Chilean judge Juan Guzman who prosecuted him after he returned to Chile in 2000.

THE DOCUMENTS

Document 1: Telcon, Helms – Kissinger, September 12, 1970, 12:00 noon.

Document 2: Viron Vaky to Kissinger, “Chile — 40 Committee Meeting, Monday — September 14,” September 14, 1970.

Document 3: Handwritten notes, Richard Helms, “Meeting with President,” September 15, 1970.

Document 4: White House, Kissinger, Memorandum for the President, “Subject: NSC Meeting, November 6-Chile,” November 5, 1970.

Document 5: Kissinger, Memorandum for the President, “Covert Action Program-Chile, November 25, 1970.

Document 6: National Security Council, Memorandum, Jeanne W. Davis to Kissinger, “Minutes of the WSAG Meeting of September 12, 1973,” September 13, 1973.

Council, Memorandum, Jeanne W. Davis to Kissinger, “Minutes of the WSAG Meeting of September 12, 1973,” September 13, 1973.

Document 7: Telcon, Kissinger – Nixon, September 16, 1973, 11:50 a.m.

Document 8: Department of State, Memorandum, “Secretary’s Staff Meeting, October 1, 1973: Summary of Decisions,” October 4, 1973, (excerpt).

Document 9: Department of State, Memorandum of Conversation, “Secretary’s Meeting with Foreign Minister Carvajal, September 29, 1975.

Document 10: Department of State, Memorandum of Conversation, “U.S.-Chilean Relations,” (Kissinger – Pinochet), June 8, 1976.

“Make the Economy Scream”: Secret Documents Show Nixon, Kissinger Role Backing 1973 Chile Coup

Related Stories

Topics

Guests

Peter Kornbluh, author of The Pinochet File: A Declassified Dossier on Atrocity and Accountability, just updated in a newly released edition for the 40th anniversary of the Chilean Coup. He is also director of the Chile Documentation Project at the National Security Archive. He just returned from Chile, and his latest article for The Nation magazine is “Chileans Confront Their Own 9/11.”

Archive. He just returned from Chile, and his latest article for The Nation magazine is “Chileans Confront Their Own 9/11.”

Links

We continue our coverage of the 40th anniversary of the overthrow of Chilean President Salvador Allende with a look at the critical U.S. role under President Richard Nixon and his national security adviser, Henry Kissinger. Peter Kornbluh, who spearheaded the effort to declassify more than 20,000 secret documents that revealed the role of the CIA and the White House in the Chilean coup, discusses how Nixon and Kissinger backed the Chilean military’s ouster of Allende and then offered critical support as it committed atrocities to cement its newfound rule. Kornbluh is author of the newly updated book, “The Pinochet File: A Declassified Dossier on Atrocity and Accountability,” and director of the Chile Documentation Project at the National Security

our coverage of the 40th anniversary of the overthrow of Chilean President Salvador Allende with a look at the critical U.S. role under President Richard Nixon and his national security adviser, Henry Kissinger. Peter Kornbluh, who spearheaded the effort to declassify more than 20,000 secret documents that revealed the role of the CIA and the White House in the Chilean coup, discusses how Nixon and Kissinger backed the Chilean military’s ouster of Allende and then offered critical support as it committed atrocities to cement its newfound rule. Kornbluh is author of the newly updated book, “The Pinochet File: A Declassified Dossier on Atrocity and Accountability,” and director of the Chile Documentation Project at the National Security Archive. In 1970, the CIA’s deputy director of plans wrote in a secret memo: “It is firm and continuing policy that Allende be overthrown by a coup. … It is imperative that these actions be implemented clandestinely and securely so that the USG [the U.S. government] and American hand be well hidden.” That same year President Nixon ordered the CIA to “make the economy scream” in Chile to “prevent Allende from coming to power

Archive. In 1970, the CIA’s deputy director of plans wrote in a secret memo: “It is firm and continuing policy that Allende be overthrown by a coup. … It is imperative that these actions be implemented clandestinely and securely so that the USG [the U.S. government] and American hand be well hidden.” That same year President Nixon ordered the CIA to “make the economy scream” in Chile to “prevent Allende from coming to power or to unseat him.” We’re also joined by Juan Garcés, a former personal adviser to Allende who later led the successful legal effort to arrest and prosecute coup leader Augusto Pinochet. See Part 2 of this interview here.

or to unseat him.” We’re also joined by Juan Garcés, a former personal adviser to Allende who later led the successful legal effort to arrest and prosecute coup leader Augusto Pinochet. See Part 2 of this interview here.

Transcript

This is a rush transcript. Copy may not be in its final form.

AARON MATÉ: I wanted to ask about the U.S. role in all of this, and let’s turn to a recording of President Richard Nixon speaking in a March 1972 phone call, acknowledging he’d given instructions, quote, to “do anything short of a Dominican-type action” to keep the elected president of Chile, Salvador Allende, from assuming office. The phone conversation was captured by his secret Oval Office taping system. In this clip, you hear President Nixon telling his press secretary, Ron Ziegler, he had given orders to undermine Chilean democracy to the U.S. ambassador, but, quote, “he just failed. … He should have kept Allende from getting in.” Listen closely.

call, acknowledging he’d given instructions, quote, to “do anything short of a Dominican-type action” to keep the elected president of Chile, Salvador Allende, from assuming office. The phone conversation was captured by his secret Oval Office taping system. In this clip, you hear President Nixon telling his press secretary, Ron Ziegler, he had given orders to undermine Chilean democracy to the U.S. ambassador, but, quote, “he just failed. … He should have kept Allende from getting in.” Listen closely.

PRESIDENT RICHARD NIXON: Yeah.

OPERATOR: Mr. Ziegler.

RON ZIEGLER: Yes, sir.

PRESIDENT RICHARD NIXON: What did you—have you said anything, Ron, with regard to the ITT in Chile? How did you handle—

RON ZIEGLER: The State Department dealt with that today.

PRESIDENT RICHARD NIXON: Oh, they did?

RON ZIEGLER: Yes, sir.

PRESIDENT RICHARD NIXON: What did they do? Deny it?

RON ZIEGLER: They denied it, but they were cautious on how they dealt with the Korry statement, because they were afraid that might backfire.

PRESIDENT RICHARD NIXON: Why? What did Korry say?

RON ZIEGLER: Well, Korry said that he had received instructions to do anything short of a Dominican-type—alleged to have said that.

PRESIDENT RICHARD NIXON: Korry did?

RON ZIEGLER: Right.

PRESIDENT RICHARD NIXON: So how did—how did that go? He put that out?

RON ZIEGLER: Well, Anderson received that from some source. Al Haig is sitting with me now.

PRESIDENT RICHARD NIXON: Oh, yeah.

RON ZIEGLER: It was a report contained in an IT&T—

PRESIDENT RICHARD NIXON: Oh, yeah.

RON ZIEGLER: —thing, but—

PRESIDENT RICHARD NIXON: Well, he was. He was instructed to.

RON ZIEGLER: Well, but—

PRESIDENT RICHARD NIXON: I hoped—but he just failed, the son of a [bleep]. That’s his main problem. He should have kept Allende from getting in. Well—

RON ZIEGLER: In any event, State has denied—

PRESIDENT RICHARD NIXON: Has State Department handled it?

RON ZIEGLER: —it today, and they referred to—to your comments about Latin America and Chile and—

PRESIDENT RICHARD NIXON: Yeah, fine.

RON ZIEGLER: —and so, you just refer to that on that one.

PRESIDENT RICHARD NIXON: Fine, OK.

RON ZIEGLER: Yes, sir.

PRESIDENT RICHARD NIXON: Right.

AARON MATÉ: That’s President Nixon speaking in 1972. Peter Kornbluh of the National Security Archive, can explain to us what Nixon is talking about here, and put it in context of the U.S. role in destabilizing Chile?

Archive, can explain to us what Nixon is talking about here, and put it in context of the U.S. role in destabilizing Chile?

PETER KORNBLUH: Richard Nixon and Henry Kissinger launched a preemptive strike against Salvador Allende. They decided to stop him from being inaugurated as president of Chile. He hadn’t even set foot in the Moneda Palace, when Nixon and Kissinger just simply decided to change the fate of Chile. Nixon instructed the CIA to make the Chilean economy scream, to use as many men as possible. The first plan was to actually keep Allende from being inaugurated as president. And then, when that plan failed, after the assassination of the Chilean commander-in-chief that the United States was behind, General René Schneider, Kissinger then went to Nixon and said, “Allende is now president. The State Department thinks we can coexist with him, but I want you to make sure you tell everybody in the U.S. government that we cannot, that we cannot let him succeed, because he has legitimacy. He is democratically elected. And suppose other governments decide to follow in his footstep, like a government like Italy? What are we going to do then? What are we going to say when other countries start to democratically elect other Salvador Allendes? We will—the world balance of power will change,” he wrote to Nixon in a secret document, “and our interests in it will be changed fundamentally.”

will change,” he wrote to Nixon in a secret document, “and our interests in it will be changed fundamentally.”

AMY GOODMAN: Talk about Kissinger’s role. Most recently, people may have seen Stephen Colbert dancing around him, the—Henry Kissinger, of course, still alive, considered an elder statesmen by most of the press in the United States. Give us a thumbnail sketch of his role.

PETER KORNBLUH: I just got back from Chile, and I did a number of TV shows there, and everybody said, “We’re trying to hold our own people accountable here for the atrocities that took place during the Pinochet regime, but why isn’t Henry Kissinger being held accountable? Why isn’t the United States held accountable for the role that they played in the atrocities that were committed in Chile, starting with the coup itself and then going on with the repression that followed?” And Kissinger really is the—not only the key survivor of the policy-making team of that era, but truly when you go through the declassified documents that are laid out in the book, The Pinochet File, you see that he is the singular most important figure in engineering a policy to overthrow Allende and then, even more, to embrace Pinochet and the human rights violations that followed.

He had aides who were saying to him, “It’s unbecoming for the United States to intervene in a country where we are not—our national security interests are not threatened.” And he pushed them away. “Nope, we can’t—we can’t let this imitative phenomena—we have to stop Allende from being successful.” He had aides that came to him the day after the coup and said, “I’m getting reports that there’s 10,000 bodies in the streets. People are being slaughtered.” And he said, “Go tell Congress that this new military regime is better for our interests than the old government in Chile.” And we have this fabulous document of him talking to Pinochet, a meeting in 1976, in which his aides have told him, “You should tell Pinochet to stop violating human rights.” And instead he says to Pinochet, “You did a great service to the West in overthrowing Allende. We want to support you, not hurt you.”

interests are not threatened.” And he pushed them away. “Nope, we can’t—we can’t let this imitative phenomena—we have to stop Allende from being successful.” He had aides that came to him the day after the coup and said, “I’m getting reports that there’s 10,000 bodies in the streets. People are being slaughtered.” And he said, “Go tell Congress that this new military regime is better for our interests than the old government in Chile.” And we have this fabulous document of him talking to Pinochet, a meeting in 1976, in which his aides have told him, “You should tell Pinochet to stop violating human rights.” And instead he says to Pinochet, “You did a great service to the West in overthrowing Allende. We want to support you, not hurt you.”

AMY GOODMAN: In The Pinochet File, you quote an assessment by the CIA’s directorate of operations, who advised President Nixon and Henry Kissinger on covert action in Chile. He argued that far from being a pawn of the communists, Allende would, quote, “be hard for the Communist Party and for Moscow to control.” He also said covert operations to stop Allende from becoming president would be, quote, “worse than useless. Any indication that we are behind a legal mickey mouse or some hardnosed play exacerbate relations even further. … I am afraid we will be repeating the errors we made in 1959 and 1960 when we drove Fidel Castro into the Soviet camp.” You also quote Kissinger’s top aide on Latin America, Viron Vaky, who wrote in a top-secret cable , “it is far from given that wisdom would call for covert action programs; the consequences could be disastrous. The cost-benefit-risk ratio is not favorable.” Peter Kornbluh?

, “it is far from given that wisdom would call for covert action programs; the consequences could be disastrous. The cost-benefit-risk ratio is not favorable.” Peter Kornbluh?

PETER KORNBLUH: That’s my point. There were people inside the U.S. government pressing Kissinger not to take this course, and he completely shunted them aside, pushed Nixon forward to as aggressive but covert a policy as possible to make Allende fail, to destabilize Allende’s ability to govern, to create what Kissinger called a coup climate.

In the new edition of The Pinochet File, we have the actual transcript of Nixon and Kissinger’s conversation, their first phone conversation after the coup took place, in which Nixon says to Kissinger, “Well, our hand doesn’t show in this one, does it?” And Kissinger said, “We didn’t do it,” referring to direct participation in the coup. “We helped them.” He says, “I mean, we helped them. [Blank],” which I am sure is a reference to the CIA, “created the conditions as best as possible.” And this is the first conversation between Nixon and Kissinger after the coup. They’re basically laying out the role of the United States and setting—creating a coup climate in Chile, facilitating the coup.

conversation after the coup took place, in which Nixon says to Kissinger, “Well, our hand doesn’t show in this one, does it?” And Kissinger said, “We didn’t do it,” referring to direct participation in the coup. “We helped them.” He says, “I mean, we helped them. [Blank],” which I am sure is a reference to the CIA, “created the conditions as best as possible.” And this is the first conversation between Nixon and Kissinger after the coup. They’re basically laying out the role of the United States and setting—creating a coup climate in Chile, facilitating the coup.

What’s even worse—this was long before your program existed, but Richard Nixon is already complaining about the liberal crap in the media, and Kissinger says, “Yeah, the liberal—the media is bleeding because a communist government was overthrown,” you know, like as if the media is on the side of Allende. They’re focusing on the atrocities that are taking place. And Kissinger says, “In the Eisenhower period, we would be heroes.”

existed, but Richard Nixon is already complaining about the liberal crap in the media, and Kissinger says, “Yeah, the liberal—the media is bleeding because a communist government was overthrown,” you know, like as if the media is on the side of Allende. They’re focusing on the atrocities that are taking place. And Kissinger says, “In the Eisenhower period, we would be heroes.”

AMY GOODMAN: In this last minute, Juan Garcés, it is interesting, though you experienced the intensity of what happened 40 years ago with Salvador Allende ultimately killing himself in the palace as the bombs rained down, you are focused on today and what is happening today—you brought Pinochet to justice. You had Baltasar Garzón, through the famous Spanish judge, issue an arrest warrant for him when he took a visit to London, and he was held there, although ultimately sent back to Chile. What lesson can we learn, in these last 25 seconds? And we’ll continue the conversation after the show.

for him when he took a visit to London, and he was held there, although ultimately sent back to Chile. What lesson can we learn, in these last 25 seconds? And we’ll continue the conversation after the show.

JUAN GARCÉS: A matter of how do you understand the world. Should you go through peaceful means or using bombs and invasions? The law is very clear. Since ’40, ’45, 1945, the United Nations Charter, after a big World War—World War—decided that the sovereignty and independence of the countries should be respected and that all the nations should fight to avoid genocidal policies.

AMY GOODMAN: We have to leave it there, but part two we’ll post at democracynow.org. Juan Garcés, Spanish lawyer , ex-aide to Salvador Allende, and Peter Kornbluh. The latest book, The Pinochet File.

, ex-aide to Salvador Allende, and Peter Kornbluh. The latest book, The Pinochet File.