The real costs of making money (5). South-African gold.

By 1914, South-Africa was the world’s top producer of gold. The increase of, mainly, South African gold production is supposed to have ended the 1873-1896 deflation, which indicates that its monetary role was crucial. But who produced this gold and at what price? What kind of labour system was used? And what where the long-term consequences of gold production?

The gold was initially produced by cheap black migrant flexworkers from, initially, all over Southern Africa as the Cape Colony (2,5 million inhabitants in 1900) and the South African Republic (1,4 million inhabitants in 1900) were far too small to supply enough labour. The number of labourers rose from about 14.000 around 1890 to around 100.000 in 1900, almost 300.000 in 1939 (and even that was not enough to prevent deflation…) to an 480.000 all-time high in 1986. Labour continued to be cheap (at least up to 1970), but especially after 1970 labour increasingly came from South Africa alone. The short and long-term social and economic consequences of the system of migrant labour were not exactly benign, the Apartheid system can i.m.o to an extent even be understood as a conscious effort to use a migrant labour system to extract rent and surplus value. Below, some excerpts from: J.S. Harington, N.D. McGlashan, and E.Z. Chelkowska, ‘A century of migrant labour in the gold mines of South Africa‘, The Journal of the South African Institute of Mining and Metallurgy March 2004 pp. 65-71.

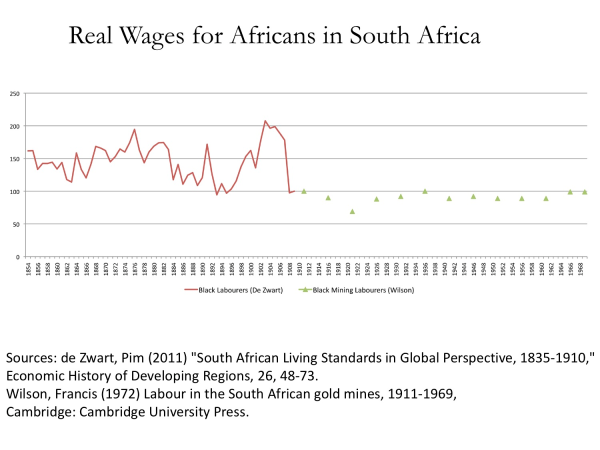

By the way: only when the migrant labour system broke down, during and after the 1899-1902 war, wages increased a little… remember this when reading the excerpts.

The historian De Kiewietin 1978 remarked that modern South Africa is built not on gold and diamonds alone but on the availability of cheap black labour…

The discovery of diamonds in 1867 gave black men chances of entering the growing cash economy, as before this farming was virtually the only employment available. In 1886, gold was found along the Witwatersrand, and this by 1914 was to make the South African gold industry the world’s top producer. … The discovery of commercial quantities of gold in the former Transvaal of South Africa in 1896 came twenty years after the exploitation of diamonds in the northen Cape.

Labour practices followed the existing migratory pattern for domestic and foreign labour in industry, a pattern which exists to this day. Gold miners, like diamond miners, were accommodated in compounds, often segregated by ethnic group, and contracted for 18-month stints with no certainty of reengagement. The source areas of these miners have for the whole of the twentieth century fallen into three political categories: men from within the borders of South Africa itself, including former black ‘homelands’; men recruited from the former High Commission, now independent territories, Botswana, Lesotho and Swaziland, who were often treated as honorary South Africans; and those from foreign countries, principally Mozambique and from as far afield as Angola, Zambia, and Tanzania. The fact that these miners came from all over southern Africa meant that the migratory system of labour would retard opportunity for men to progress up the ladder of skills and would for a very long time establish that the barrier of colour became also a barrier to advancement.

The data all support the contention that the migrant system is untenable, pervasive and regrettable, certainly not a temporary system, but an entrenched and fundamental one with serious social costs. It has become a permanent feature of life for millions of workers …

In 1890 the number employed was 14 000. By the end of that decade this number had increased sevenfold and by 1998 the total stood at 255 000, a drop of 42 per cent from its peak of 534 000 in 1986. In essence, the labour policy required sufficient and stable numbers over regular periods. The only alternative to this mass movement was the large scale resettlement of the miners and their families along the Reef, but this was economically suspect to the mine owners and politically unacceptable to successive South African governments. Consequently, the attainment by the mining industry of its desired ends in labour numbers depended on men migrating continuously back and forth from several countries in southern Africa, notably Mozambique and Lesotho, as well as from all over South Africa itself. A similar picture exists in the former Transkei and Ciskei (the present Eastern Cape), now devastated by the legacy of migrant labour, which robbed the area of its economically active men and left women to eke out a dismal living from subsistence farming …

The South African War of 1899–1902 forced every gold mine into a virtual shutdown and led to a lowered demand for black labour and the loss of over 100, 000 jobs … By 1903 the black labour force was down to half the 90 000 of 1899 …. Morbidity among black workers, chiefly due to pneumonia, tuberculosis and diarrhoeal diseases, remained generally high. To try to resolve this serious labour shortage, an ill-fated but shortlived immigrant Chinese system was introduced in 1904, reaching its peak in 1907 and failing by early 1910 when the last Chinese worker returned home. The venture failed mainly because of the political shock waves it engendered in England where open hostility was expressed in influential quarters at what were termed the slave-like conditions of employment of Chinese workers. Since at that time black labour was still hard to come by, WNLA continued to recruit from the southern provinces of Mozambique, with stringent health checks before miners were accepted.

In addition to the inherent dangers of work underground—in 1907 mortality ran at 470 per 100 000 employees per annum—were the recognized dangers of high pre-existing pneumonia rates … Initially for paternalistic, but latterly for legal and social reasons, mine management has always provided health care for its employees, building, staffing and administering some of the best hospitals in the continent. … The violent events of the Afrikaner Rebellion in 1914, the protests of Gandhi, the General Strike in 1914, and an earliermine strike in 1913 had all disturbed the status quo of the total labour force. Grievances were many, and ameliorative recommendations followed, all of this overtaken by the outbreak of the Great War in 1914. For the mining industry the four years to follow were times both good and bad. Number of miners stabilized, trade unionism began to strengthen, and the effect of the Great Depression of the 1930s was soon to follow. ‘In this scenario of economic tragedy, gold mining staved off total disaster’. The number of black workers in the mines actually rose in each of the Depression years and reached new peaks from 1932 to 1940. White labour, too, rose by the year. The demand for gold at its then standard price of £4 4s was ‘infinite’. By 1932 South Africa and its highly cost-sensitive gold mining industry were enjoying a windfall. In that year the country departed from the Gold Standard, new gold-bearing formations were found, and the gold price rose. These windfalls gave industry perhaps its greatest boost ever and ‘seven golden years’ of expansion followed. Black employment increased as a result, reaching a new peak of over 360 000 in 1939–40. But World War II brought grave repercussions. Worker dissatisfaction and employees leaving the industry was one symptom and a shortage of supplies another. The peak of mining operations and its labour fell away from 1941 and stayed depressed until the mid-1950s. Although South Africa came out of the war reasonably well, the gold price was low and conditions for labour were poor, strikes broke out; one in 1946 involved 60 000 of the 300 000 men in the mines, bringing nine mines to a standstill and partially affecting eight others. At the same time a cost-price squeeze and slender profit margins were seriously impairing the effectiveness of the industry. A further upset occurred in 1948 when D. F. Malan’s National Party won the general election by 70 seats to the United Party’s 65, and little more than two years later, J.C.Smuts died. Although black-white issues were to be severely affected for decades by these events, ironically for the mining industry, more prosperous days lay ahead, ushered in by a rising gold price and huge worldwide expansion. South Africa’s market policy in 1973 contributed much to the rapid rise of the gold price to above US$100 an ounce. This was followed by vigorous trading, which was to usher in the ‘renaissance of gold’ in the rest of the seventies, starting with the introduction of the Krugerrand in 1970. In 1974 the Chamber launched a drive for South African blacks to replace foreigners. TEBA then gradually reduced the foreign component of the total labour force, which fell from 37 per cent in 1966 to 16 per cent by 1979. This change had already been initiated by President K. Kaunda in 1967, stopping Zambian labour to the gold mines and was further prompted by a WNLA Skymaster crashing in 1974 with the loss of 74 Malawian miners and the aircraft crew. President H. Banda of Malawi immediately banned further engagement of Malawians in the mines, 129 000 miners being affected…. Within both Zambia and Malawi these changes of policy had major economic and political consequences, with unemployed men and their families becoming virtually destitute. By the mid-eighties, the demand for gold was robust, helped by the weakening South African rand exchange rate. The gold mining industry earned R14 billion in 1985 and paid an estimated R3.4 billion to the state in tax and share of profits. The potential for new jobs was obvious: the total mining industries, gold, platinum, uranium and other minerals earning some R26 billion and having some 700 000 people employed. Within this huge total was the highest peak of black gold mine workers ever attained since the discovery of gold a century before, some 480 000 workers per annum over 1987 to 1988 In 1984 the black labour force stood at 437 000 men. By 1994, the last year in which black workers were classified apart from whites, the total black force was 303 000, of which 156 000 (51 per cent) were South African. .. In total, however, the gold mining industry, once the country’s largest employer, had reduced its black worker numbers from 477 000 in 1986 to 303.000 in 1994 …. Between 1985 and 2000, the value of mine output had increased by more than 250 per cent, whereas employment had fallen by 50 per cent … The 1990s brought further swarms of disgruntled and unemployed miners back to their villages in vast and unexpected numbers to the loss of mining opportunities documented in our paper. Land erosion and deterioration, and consequently further falls in agricultural productivity, are already seen as results of this newly induced population pressure.

recently published data, shows a continued decline of all labour, black and white, to the year 2000.