Septtember 8, 2014

Economics textbooks are not only written for students. At two critical points in the history of economic thought textbooks have played significant roles in defining the field, not only for what is taught, but more importantly (in terms of real world outcomes) for the understanding of the economy that is used by politicians, policy makers, and the public, when it votes its approval or disapproval of how the government is affecting the economy.

This started in the 1890s, when Alfred Marshall wrote the first edition of his text, called Principles of Economics. It went through 8 editions, the last being published in 1920. For a large part of the English-speaking world Marshall’s textbook continued to define the field (especially the microeconomics basics) until the middle of the 20thcentury, when it was replaced by Paul Samuelson’s Economics (first published in 1948). That set the standard for about the next 60 years.

These textbooks have not only defined economics for students, they also set clear standards for how people in general should think about the economy, having great influence on government policies and also on the economic research that supports policy. Samuelson was well aware of the impact of his texts, saying in an introduction, “I don’t care who writes a nation’s laws – or crafts its advanced treaties – if I can write its economics textbooks.” Every year about 5 million people in the U.S. graduate from college having taken at least one economics course. These courses, and the textbooks that shape them, in turn contribute to a shared understanding of how things work in the world – and to a general consensus on whose voices will be heard on economic subjects.

Consider, for example, what might be called “Obama’s dilemma”: If you are not, yourself, deeply immersed in economics, how do you select economists to advise you on policy? Should President Obama have chosen his advisors based on reputation in the discipline? Or on personal economic success? I don’t pretend to know in any detail what political constraints or motivations would have dictated what the president asked of his advisors, but it appears that he relied on both of these screens. Based on the first screen – reputation in the discipline – his choices would not have included anyone thinking about the new economy of the future, for the discipline has closed ranks very firmly around insiders, providing little opportunity for academic outsiders to become widely known. The second standard – being good at making money – moved him to select a number of his advisors from Wall Street, which has in recent years been among the most lucrative areas for amassing modern fortunes. If economics is about money, then, the reasoning goes, financiers must know a lot about it.Without trying, here, to assess the effectiveness, or the goals, of Obama’s economic policies, I will simply note that the problems in the economy that led to the 2007 crash and the Great Recession have not been solved; bubbles keep building up, enriching some people in the short run, and creating the potential for, once again, severe economic suffering for “main street” in the not so distant future. Neoclassical economic theory has failed to anticipate a number of severe problems that have been building up over the time of its intellectual dominance. To name just a few of the trends that have resulted from the system supported and celebrated by neoclassical economics, these include:

- ever greater income and wealth inequality;

- ever greater concentration of economic and political power in ever larger corporations – with severe negative impacts on the operation of democracy;

- a global climate that is rapidly changing in ways that threaten human health, the viability of many cities, the agriculture systems that feed humanity, and the diversity of plant and animal species on earth.

We are now at a time when economics is in need of another 60 year refresh. The heart of this need is in the question: How are human motivations and behavior to be understood in this human science?

from

Neva Goodwin, “The human element in the new economics: a 60-year refresh for economic thinking and teaching”, real-world economics review, issue no. 68, 21 August 2014, pp. 98-118, http://www.paecon.net/PAEReview/issue68/Goodwin68.pdf

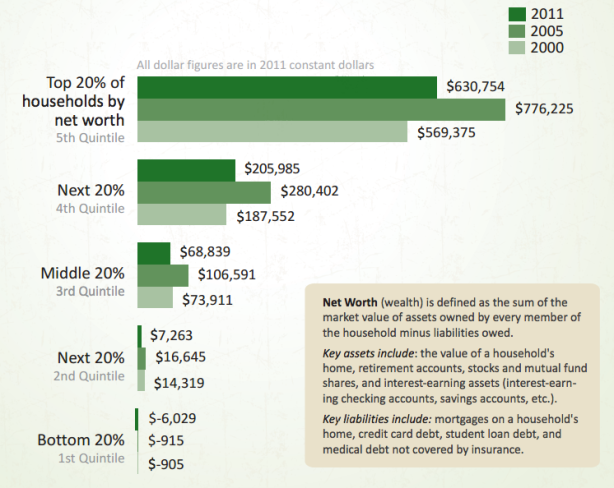

USA median household’s net worth fell from $106,591 to $68,839 from 2005 to 2011

September 8, 2014Leave a commentGo to comments

from David Ruccio

As Danielle Kurtzleben explains,

the median household’s net worth fell from $106,591 to $68,839 from 2005 to 2011. . .

the median net worth of the top 20 percent divided by the median of the second 20 percent was 39.8 in 2000. Today, it’s 86.8.

In addition, the latter group lost nearly 56 percent of its wealth. And the overall wealth of the bottom 20 percent fell from -$915 to -$6,029. Or, put another way, the median American in that poorest group saw their debt

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES FROM STTPML:

regression and causality ChenPearl65

causality and regression analysis Syll64

capitalism and human extinction Smith64

excess capital and inverted fascism Robinson67

capitalist world economy wallerstein 9780521220859ws

rise and future demise of world capitalist economy Wallerstein

world systems wallerstein THYTLK13

UnderstandingCapitalismInstructorsManual

political economy of capitalism 07-037

The Foundations of Capitalist Economy

trading with the enemy higham TWTE_Complete

Conf of Mayors Report 2014 Wage Gaps and Unemployment report

Karl Marx´s Grundrisse – Foundations of the critique of political economy 150 years later

terrel-carver-karl-marx-texts-on-method

0521366259.Cambridge.University.Press.The.Cambridge.Companion.to.Marx.Nov.1991

homo economicus and human evolution Mezgebo67

RadicalPoliticalEconomicsOfDFD

Marxism for the few let them eat theory

doug dowd world problems and us power cliffs_edge00-03

capitalism-and-its-economics-a-critical-history-douglas-dowd

articles and separating pepper from fly droppings img248

The_Development_of_Modern_Propaganda_in_Britain,_1854-1902_-_FINAL_CORRECTED_THESIS

SearchForTheManchurianCandidate

Antony Sutton – Wall Street and the Bolshevik Revolution 1974

The Doctrine of Fascism – by Benito Mussolini (Printed 1933)

Bohemian Grove and Other Retreats

The Brotherhood and the Manipulation of Society – CFR – BILDERBERG GROUP – TRILATERAL COMMISION

diagrams in economics Pullen65

Indigenous Epistemology and Scientific Method pdf

imperialism brenner-what_is_and_what

From_Political_Economy_to_Freakonomics

Der Anti-Samuelson- Kritik eines repräsentativen Lehrbuchs der bü

David Hawkins – Power Vs Force

Corporate_Power_in_a_Global_Economy

mathscience in 21st century Connect_2010_Jan-Feb

InternationalEducationTranslation

David_Miller_and_Rizwaan_Sabir-Propaganda_and_Terrorism-2012

old vs new paradigms in economics Fullbrook66

WorldinBalanceSheetCrisisRWER58Koo58

Neoclassical Economics Death of Colander

Neoclassical Economics and Neoliberalism as Neo-Imperialism (2)

eprint of international ed and imper 21598282.2011

Critiques of Steve Keen and NC Economics Chinese version img257

Critiques of Keen and NC Economics English img256

The anti-Samuelson. Volume One. Macroeconomics- basic problems of

The anti-Samuelson. Volume Two. Microeconomics- basic problems of

NASA study Industrial Collapse handy-paper-for-submission-2

Citibank Plutonomy Report Consolidated

BernaysEdward-Propaganda192879P.Scan

13285654-Antony-Sutton-Wall-Street-and-FDR

5369599-Crystallizing-Public-Opinion-Edward-Bernays

presentation-at-tsinghua-aug-2012 (1)

44_Carroll_Quigley___The_Anglo_American_Establishment

CIAsubversionmanualnonviolentstruggle

CIAsubversionmanualcorecurriculumstudentsbook

Citigroup-Plutonomy-Report-Part-1

Citigroup_Plutonomy_Report_Part_2

citibank plutonomy symposium memo3

Theoretical System of Marx and Engels, completed and proofed.(3) pdf

Wealth_and_Illfare_CTKurien_2012_ebook

Don’t rock the ideological boat (too much)

Don’t rock the ideological boat (too much)

By David Wells

In his opening keynote address at the recently-concluded Rethinking Economics conference in London (June 28-29, 2014), Lord Adair Turner dismissed the need for changes to microeconomics by referring to the beneficial use made of micro by two committees he chaired, the Pensions Commission and the Low Pay Commission.

His committees may well have benefited from microeconomic insights but that does not leave micro in the clear. After all, the centrepiece of the micro banquet is the model of perfect competition which is foundational for the theory of General Equilibrium which in turn lies behind those models which assured mainstream economists that the financial crash of 2008 was not merely unlikely but actually logically impossible: so micro has a lot to answer for.

Lord Turner then focused his attention entirely on macroeconomics. The obvious problem with this limitation is that it leaves most of the foundations of mainstream orthodox economics intact and so student rebels against orthodoxy are likely to be disappointed.

Every session I attended at the conference included at least one reference to ideology. In addition, ‘Whig’ as in Whig history was heard at least once, and ‘neoliberal’ several times.

Yet no-one put these themes together to actually come out and say plainly that the ideology of mainstream economics is (extreme) liberal, let alone to argue that this ideology which naturally and inevitably promotes laissez faire and free markets and so on, leads to distorted and inadequate models of experience, as seen in current economic textbooks and in the 2008 crash.

Ha-Joon Chang in his concluding keynote called forcefully and eloquently for pluralism in economics teaching, without considering that some of the schools of thought within economics that he identified preach (the correct word) ideas and claims that are deeply ideological and deeply damaging, the prime culprit being the hegemonic and extreme liberal neoclassical school. Thus, I presume that DSGE models ought not to be included in any pluralist course, except possibly as a terrible example of ivory tower economists running amok.

Finally, just before the final keynote address, a short video was played in which Robert Johnson, the President of INET, sent his best wishes to the conference and congratulated the organisers – but also suggested at one point that the students should be ‘guided’ by INET.

This is strange. Why should the students be ‘guided’ by INET ? Why not the other way around? After all, it is the students who are the instigators of this revolution and who are at the front line, manning the barricades. INET are very active in their own way – the CORE curriculum project is especially interesting – and they supply invaluable funding, including for this conference2, but they are essentially secondary actors on the stage. The protagonists are the students, not just in the UK but all over the world: the ISIPE now has (at least) 65 member associations in 30 countries.

Putting these points together, and writing as one of the older generation who was actually there at the time, I am reminded of the 1965 essay by Herbert Marcuse on ‘Repressive Tolerance’.

Lord Turner is happy to use his vast experience to re-examine macroeconomics, but the foundations are, frankly, OK. Everyone acknowledges that ideology is present, but no-one actually wants to analyse it deeply. Robert Johnson wishes the students well but hopes that they will accept his avuncular guidance, while Ha-Joon Chang favours pluralism but without examining any ideological skeletons that various schools might be hiding in their cupboards.

If I were a student, I think that I would find this extremely disturbing.

1 Reposted from the Rethinking Economics Blog

2 And for researchers. I applied for a grant myself and was rejected, probably quite rationally.

From: p.5 of World Economics Association Newsletter 4(4), August 2014http://www.worldeconomicsassociation.org/files/newsletter/Issue4-4.pdf

Damien Cahill interview on neoliberalism

Damien Cahill is the author of The End of Laissez-Faire? On the Durability of Embedded Neoliberalism, published in September 2014 by Edward Elgar. He has a blog at:http://damiencahill.net/. Here he answers some questions from Newsletter editor Stuart Birks:

- What do you understand by the term neoliberalism? Is it what people refer to as ‘mainstream economics’?

Neoliberalism has several dimensions. First, it is a set of ontological doctrines about how the economy and society more generally operate, and a set of utopian normative visions about how it should, ideally, be organised. Second, neoliberalism is a policy regime marked by the microeconomic processes of privatisation, deregulation, marketisation and macroeconomic policies of inflation targeting and an end to full employment as the proper goal of states. Third, neoliberalism is a set of economic transformations whereby capital has been freed from many of the constraints upon its ability to operate within and between borders that had been in place during the post-World War II economic order. Clearly, these three dimensions of neoliberalism are interrelated.

As a doctrine there is significant overlap between neoliberalism and mainstream, or neoclassical, economics. Indeed, to a very great extent, neoliberal doctrine entails taking the foundational principles of neoclassical economics to their logical conclusion. At its heart, neoclassical economics proposes a situation in which asocial individuals voluntarily exchange with one another through markets for mutual benefit. State regulations, other than the provision of basic framework of rules, are cast as an exogenous interference in this otherwise self-regulating system. Neoliberals have taken this idea and argued that such a free market system is not only the most efficient way of organising the distribution of goods and services, but also the most moral, since it is the best way of preserving individual liberty (when defined negatively as freedom from coercion). From this follows the policy proposals of privatisation, marketisation and deregulation – that is, engaging private capital in the provision of public services and freeing it from constraints that prevented from doing so efficiently.

One should not ignore however the influence of other currents of thought in the development of neoliberal doctrine – especially that of Austrian economics, predominantly via Friedrich Hayek’s work. In contrast to neoclassical economists, Hayek was skeptical of the ability of humans to understand the world or complexity through the application of reason. This is actually at the heart of his defence of and preference for a market order. According to Hayek, it is only the unhindered operation of the price mechanism that allows for the multiplicity of subjective individual preferences in a large complex economy to be registered and responded to. So, he arrives at a similar policy conclusion to that of a fundamentalist neoclassical economist like Milton Friedman, but by a different route. Where he and Friedman did differ over policy was with respect to the proper role and size of the state. Whereas Friedman advocated a fairly consistent ‘small state’ line, Hayek believed that a range of state forms were consistent with the maintenance of a competitive market order.

- Do you see it as having a theoretical foundation, or is it more a political and ideological phenomenon?

While many neoliberal politicians (Margaret Thatcher is a case in point) have certainly been inspired by and influenced by the writings of neoliberal fundamentalists like Friedman and Hayek, it is important to distinguish between neoliberal theory and practice.

On the one hand, there are clearly correlations between the two. For decades, neoliberal intellectuals advocated policies of privatisation, deregulation and marketisation and, indeed, this policy suite has become the common sense of state regulators across the capitalist world. On the other hand however, the more closely one scrutinizes ‘actually existing neoliberalism’, the more problematic is the fit between neoliberal theory and practice.

If we take neoliberal doctrine to be promoting a small state agenda (something certainly advocated by Friedman and many of the major neoliberal think tanks), then it is clear that this vision has not been realized. Not only has the economic size of the state not been reduced under neoliberalism, but neoliberal policies of deregulation, privatisation and marketisation have almost always entailed augmentation of new forms of social and economic regulation and the construction of new institutions to regulate markets in which newly privatised entities will operate.

If, however, we instead look to Hayek for the foundations of neoliberal doctrine, then we end up with all manner of state forms potentially being justified – from the authoritarian state of Pinochet’s Chile, to Sweden’s social democratic welfare state – so long as they facilitate the expansion of a capitalist market order. The problem here is that no test of causation is really possible, as Hayek doesn’t offer a blueprint.

This is why I think the most satisfactory way to understand role of neoliberal ideas in the construction of the neoliberal policy revolution is in ideological terms. The neoliberal doctrines of Hayek, Friedman and others provide a highly malleable set of discursive tools that have been selectively appropriated to justify neoliberal policies in both philosophical and economic terms. The neoliberal policy regime has therefore become embedded within a powerful and pervasive ideological matrix.

- Why do you see it as being embedded?

The policy regime of neoliberalism has proven to be highly durable, even in the face of the crisis that has beset the global capitalist economy since 2007. When this crisis hit, many believed that neoliberalism had been forced onto its last legs – that the global financial crisis as a sign of failure heralded its decline. Those who predicted that the crisis signaled the end of neoliberalism have been hard-pressed to explain its subsequent resilience. One reason for this, I believe, is that they grounded their analysis primarily in the realm of ideas. In doing so, they mistook the decline in legitimacy that neoliberal ideas certainly underwent after the onset of the crisis, for a retreat from neoliberalism more generally.

Such commentators missed the ways in which the neoliberal policy regime has become deeply socially embedded, not simply in a pervasive ideological framework, but also within new institutional rules and a reshaped set of class relations. This has given it enormous inertia. By institutionally embedded I mean not only that states have developed new neoliberal regulations but, more importantly, they have enacted or signed up to a framework of rules that commit governments to further neoliberalisation, irrespective of their political colours. Competition policies and the articles and rules of supra-national institutions such as the World Trade Organisation, the economic constitution of the European Union, and the numerous ‘free trade’ agreements to which states are increasingly signatories are examples of this institutional embedding of neoliberalism.

As for the embedding of the neoliberal policy regime within class relations, this refers to ways in which the profit making strategies of capital have come to depend upon the maintenance or extension of neoliberal forms of economic regulation, as well as the fact that the ability of capital to achieve this goal has been bolstered by the strengthening of its political power, and well as its power within the employment relationship.

- What alternative perspectives might there be?

In my view, the alternative to neoliberalism is decommodification through the quarantining of people’s livelihoods from market dependence. This can be achieved by nationalization, direct state provision of services as well as various forms of social protection in areas such as finance, housing, education and healthcare. There is no shortage of good ideas among progressive economists for realizing these aims, including financial speculation taxes, guaranteed minimum wage schemes, and various proposals for capturing the surpluses circulating in the financial sphere of the economy and directing them towards socially beneficial investment. Moreover, the broad family of heterodox economic approaches offer a far richer understanding of actually existing capitalism than do neoliberal doctrines, not to mention that they provide a range of policy options focused upon the needs of ordinary people, not just those of the 0.1% of the population.

- Do you see change being possible in the short term?

The onset of the global economic crisis has actually opened a window of opportunity for progressive, non-neoliberal change in the short term – but such change is by no means guaranteed. The crisis has demonstrated the perils of the market dependence that has been such a key feature of neoliberalism. It has exposed the power imbalances and inequalities at the heart of the capitalist polity and economy. And it has seen state elites turn to nationalization, a political dirty word prior to the crisis, in order to save the capitalist system from collapse. Although none of the nationalisations conducted by the major capitalist powers in response to the crisis have resulted in the enterprises operating for need, rather than profit, the turn to nationalization has, I believe, given a legitimacy to this form of policy that didn’t exist in the two decades prior to the crisis.

Nonetheless, it must be acknowledged that the dominant form of crisis response by states has been further neoliberalisation, including privatization, deregulation and austerity budgets that are eroding working class living standards. For me, that states have turned to neoliberalism in the face of a crisis that was itself the result of such policies underscores the durability of the neoliberal policy regime.

But it also suggests that good ideas alone won’t be sufficient to dislodge neoliberalism from dominance. Non-neoliberal ideas will need to be allied with and carried forth by strong social movements. We’ve already seen glimpses of this – from the occupy movement, to the anti-austerity protests in Greece and elsewhere in Europe, to the mobilisations against anti-labour laws in the USA as well as the post-crash economics movement. So there are reasons to be hopeful that after the devastation and despair brought about by the crisis, neoliberalism can be consigned to the dustbin of history.

From: pp.2-3 of World Economics Association Newsletter 4(4), August 2014http://www.worldeconomicsassociation.org/files/newsletter/Issue4-4.pdf

C T Kurien and real life economics

By Stuart Birks

Kurien may not be well known outside India, but his highly readable work over many decades highlights limitations in mainstream economics. The publisher of his recent book, Wealth and Illfare: An Expedition into Real Life Economics (Kurien, 2012), has provided a pdf of the book for wider circulation. It is available free for download from the World Economics Association website here.

On the face of it, the book is an introduction to economics. In reality it is an accessible outline and critique that incorporates aspects of alternative approaches to economics.1

It does not present these alternatives as competing schools of thought. Instead, Kurien indicates how the framing of mainstream economics overlooks important factors which are addressed elsewhere. Pluralists are likely to appreciate this perspective and it may lead some mainstream economists to reassess their interpretation of the dominant theories.

The book is in four parts, plus a conclusion, but I see it as having three sections. The first includes Parts I to III and develops a picture of economic activity by means of ‘thought experiments’. The result is a story outlining the evolution of economic relations as primitive pastoral communities develop into more complex, interconnected societies with division of labour and differences in income and wealth. The context is India, but that has its own advantages. Readers from elsewhere are drawn into a representation of social evolution uncluttered by their views of their own history. Presumably this was not Kurien’s intention. Nevertheless, it can be effective. Such detachment has been deliberately used in political writing for centuries in literature such as Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress and Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels, not to mention Voltaire’s Candide.

The motivation for his approach is clear when contrasted with mainstream theory and its emphasis on a supposedly ideal system of markets in perfect competition. This latter is highly abstract. In 1966 Kurien critically assessed the nature of this approach relating it to Koopmans’ (1957) ‘postulational method’. In a series of lectures he presented it using a line of reasoning:

“…that theories are propositions derived from a model, and that a model is an ordered set of classes defined by the postulates. It is in this ‘universe’ and only in this universe, set up by the postulates, that theory, even in its purest state, has unconditional generality.” (Kurien, 1970, p. 24)

He describes theory as having two distinct aspects, the syntactical which uses logic to draw conclusions from propositions, and the semantic where the theory is related to the real world. We could conclude that Kurien has reservations about the semantic stage in mainstream economics. He would contend that the syntactical findings are being applied widely to real world problems without considering their applicability in specific instances.

Kurien’s thought experiment considers aspects of mainstream thinking, but his narrative clearly indicates the role of ownership, intermediation and asymmetric information. In a farming-based society some people have surplus land and are in a strong bargaining position. Some are at the other extreme, having no land and little bargaining power. This can lead, in time, to increased inequality. Similarly, when surpluses are taken to town to be traded, one farmer may take the surplus on behalf of a group of farmers. This person may gradually assume the role of sole buyer from the other farmers and gain more knowledge of the market where the produce is sold. Such specialisation can result in increased power and wealth for this person. Also, when farmers need loans to carry them through to harvest, those with funds are in a strong bargaining position and can set the terms of the loans. Structures and hierarchies develop benefiting some and penalising others.

Kurien’s narrative is of evolving social and institutional arrangements. The purely economic dimension is just one aspect of the whole. As such, Kurien not only gives a context for mainstream economics, but also highlights its limitations.

The second, shorter, section of the book is contained in Part IV. It describes the Indian economy as a whole, stressing that “Real Life Economics is unavoidably political economy”. Kurien looks at some of the data and challenges the perception of high growth in recent years. A breakdown by sector indicates that, while GDP has been increasing rapidly, the benefits have been concentrated in a small part of the economy, in particular the high-tech area. Meanwhile, much of the population has faced significant disruption and is actually worse off than in the past. Moreover, Kurien argues, growth should not be seen simply in terms of numbers, but rather as a ‘societal process’. It “impacts different sections of people differently apart from having tremendous ecological implications”.

Mainstream economics, by narrowing down the parameters of the analysis, fails to consider wider, dynamic, social and other implications such as these. In particular, the atomistic treatment of individuals conceals the importance of interactions and people’s place in society. I was recently at a symposium on neoliberalism in which it was asked why neoliberal ideas had become so dominant. One reason might be the dominance of a small number of core textbooks which comprise, for many students, their only exposure to economics. They are given ever shorter courses giving a narrow perspective with little or no recognition of limitations and alternative viewpoints.

The third section is the conclusion. It is shortest and might come as a surprise to some. It is where Kurien looks forward while also being at his most critical. He contends, with some justification, that dominant economic theories justify the capitalist economic order while failing to recognise the role of intermediation. This failing in the theory, along with capitalism’s characteristic of ‘dehumanisation’, lead him to look for alternatives. His recommendations are not as radical as some might expect. He has drawn attention to several phenomena, such as those that lead to increasing inequality and to lack of regard for social dimensions of society. He sees greater emphasis on these as a way to ensure that economic activity benefits many, rather than only a few.

Any framing emphasises some aspects and excludes others. Alternative framings can be useful for broadening our understanding. Inevitably, some will wish to challenge some of Kurien’s specific points and perhaps even the whole approach. However, his work highlights limitations of mainstream thought in a stimulating and accessible way. He also introduces readers to heterodox economics without overtly naming the alternatives. The uninitiated may be more receptive to such an approach in that it avoids the risk of preconceived judgements. Kurien is one of a large number of writers who present alternatives to the mainstream. It would be good to see such reading incorporated into the standard curriculum.

Hare, P. (2012). Vodka and pickled cabbage: Eastern European travels of a professional economist [Kindle edition] Retrieved from http://www.amazon.com/Vodka-Pickled-Cabbage-Professional-ebook/dp/B008IGP6RK

Koopmans, T. C. (1957). Three essays on the state of economic science. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Kurien, C. T. (1970). A theoretical approach to the Indian economy. London: Asia Publishing House.

Kurien, C. T. (2012). Wealth and illfare: An expedition into real life economics. Bangalore: Books for Change.

1 A similarly accessible book that questions the direct application of mainstream economics is Hare (2012).

From: pp.6-7 of World Economics Association Newsletter 4(4), August 2014http://www.worldeconomicsassociation.org/files/newsletter/Issue4-4.pdf

2 responses

Economics: The User’s Guide by Ha-Joon Chang – reviewed

Review by Juan Carlos Moreno-Brid (Deputy Director, ECLAC-Mexico).

Opinions here expressed are the author’s responsibility and do not necessarily coincide with those of the UN.

Thanks! That’s the word that came to my mind when I finished reading this original, valuable text. It comes to fill a void in the toolkit of any lecturer to college students and non professional audiences interested in economic development and policies. With a unique mixture of recognition of the merits of alternative economic theories, reverence for historical facts, systematic reference to real-life numbers and an enviable sense of humor, Ha-Joon Chang manages to present economics as a user friendly, relevant and passionately exciting craft!

Through carefully sequenced chapters, spiced by illustrative quotes from novels, newspapers, speeches, movies and TV series, the Guide exposes the reader to economics’ fundamental concepts, actors, ideas and transformations. This exposition evidences that valuable conclusions on key real-life issues – concerning nations, firms, states, classes or individuals – can be drawn from a discursive application of alternative economic theories.

Combined with excellent narrative capacities, this comprehensive view of alternative economic theories plus attention to political and historical considerations, the User’s Guide is an important vehicle to discover Economics as a relevant, useful practice. Perhaps its major contribution is to emphasize that there is no unique, intellectually correct, economic theory, applicable urbi et orbi. On the contrary, there are many analytically robust economic theories, , though supported by different assumptions in particular on who are the dominant actors in the economy, how they set their goals and interact to meet them under social, political and historical constraints and in a climate of uncertainty.

Economics: the User’s Guide is characterized by a conspicuous absence of algebraic formulae, equations, diagrams, figures and statistical tables. Instead, its arguments are presented through discursive reasoning relying on a variety of economic theories. The approach seemed explicitly chosen so as not to scare mathematically shy students and also to emphasise that economics is not an exact science of mathematical precision. It succeeds on both grounds. Economics is presented as a heterogeneous, friendly and far from solemn discipline with a toolkit derived from a gamut of alternative theoretical frameworks aimed at understanding real-life economic challenges: unemployment, poverty, inequality, and financial crises. This collection of alternative theories is tailored to understand the world economy and, if possible, to change it.

The emphasis on the diversity of economic theories and on making persistent reference to real-life data has additional benefits. On the one hand it trains the reader to pose different questions about real-life economic situations. On the other, and most important, it invites him or her to examine them from multiple angles and to try to answer them by relying on contributions from the different economic theories examined in the book.

The analytical toolkit presented in this book broadens the reader’s capacity to understand major economic problems and principles. It does this much better than the standard introductory textbooks where utility and profit maximizing agents interacting in perfectly competitive markets are at the core of economic analysis, where reference to real-life data is the exception, and where the importance of historical, political or ideological influences tends to be minimized or dismissed.

The book is organized in two parts, plus an epilogue. The first part introduces the key tools and actors of the economy. Two of its elements are in stark contrast with mainstream approaches. The first is the inclusion of a succinct, well written history of capitalism. This inclusion, as the author states, is done based on the firm conviction that, in order to understand the current state and prospects of any given economy, one must be aware of its history, how it came to be. History has no substitute for understanding the constraints that are faced for assessing, to an extent, the room for maneuver with policy options. Recognition of the relevance of history is largely absent in mainstream introductory books.

A second even rarer trait of Part 1 is the identification and detailed explanation of the main alternative schools of economic thought: Classical, Neoclassical, Marxist, Developmentalist, Austrian, Schumpeterian, Keynesian, Institutionalist and Behaviouralist. The assumptions, theoretical basis, strengths and limitations of each one are briefly but deeply analyzed.

The second Part sees the tools applied to analyze key issues, ranging over economic welfare, the role of industry, work and unemployment, finance, inequality and poverty. In this Part the author identifies key debates that have shaped, or are still shaping, our views on the issues explored. This second part closes with a discussion of the roles of the State and the market in the economy, as well as the relevance of the international economy.

The epilogue stresses the merits of methodology adopted. I would stress three recommendations. 1. “Economics is a political argument”. Thus in the analysis of any economic decision or policy prescription, one should always find out who will benefit from its application. Who benefits from applying or not applying a specific policy or agenda is at least as important, and perhaps even more so, than any efficiency or efficacy considerations posed in this context. 2. The diversity of economic theories is a plus in the analysis of economic problems and principles, by allowing the possibility to focus on different aspects with different methodologies. 3. A fundamental piece of advice is that people should use the new knowledge to become “an active economic citizen” that pushes for better economic policies.

Developing countries, including Mexico, would be more likely to succeed in their quest for economic growth cum equality if economic leaders read this simple, original, most valuable contribution by Professor Chang, absorb the advise and thus “learn how to think, not what to think about economics…”.

In this regard, and posing the key question, Cui bono? Who benefits from this book? Many, many audiences. In particular young students in high school or early years of college, eager to understand economics in order to try to change the world! No introductory book would be better to fulfill their enthusiastic expectations and build their knowledge of the various economic theories and their applications to understand the world. Whether they will eventually transform it, is a different matter. In any case, again, Thanks.

From: pp.11-12 of World Economics Association Newsletter 4(4), August 2014http://www.worldeconomicsassociation.org/files/newsletter/Issue4-4.pdf

As the author of the book I appreciate Stuart’s review bringing the book to the notice of a larger community of concerned economists outside India. I would however point out that the three concepts I have used to understand real life economics are Ownership (not Power as Stuart states) Intermediation and Asymmetry of Information, all of which are overlooked in the traditional approach to economics. Power is important, but in the economic realm it arises from ownership of resources and the ability to manipulate information.

Thanks CT. I acknowledge the error and have altered the text. Your book makes the point very clearly.